A Suggested Interpretation of Pilling in Mediaeval Times

by RC Watson

The following article is the writer's view of how Pilling was perhaps organised during the mediaeval period. It is a preliminary exercise, and is intended to offer a basis for further serious study, perhaps by other individuals.

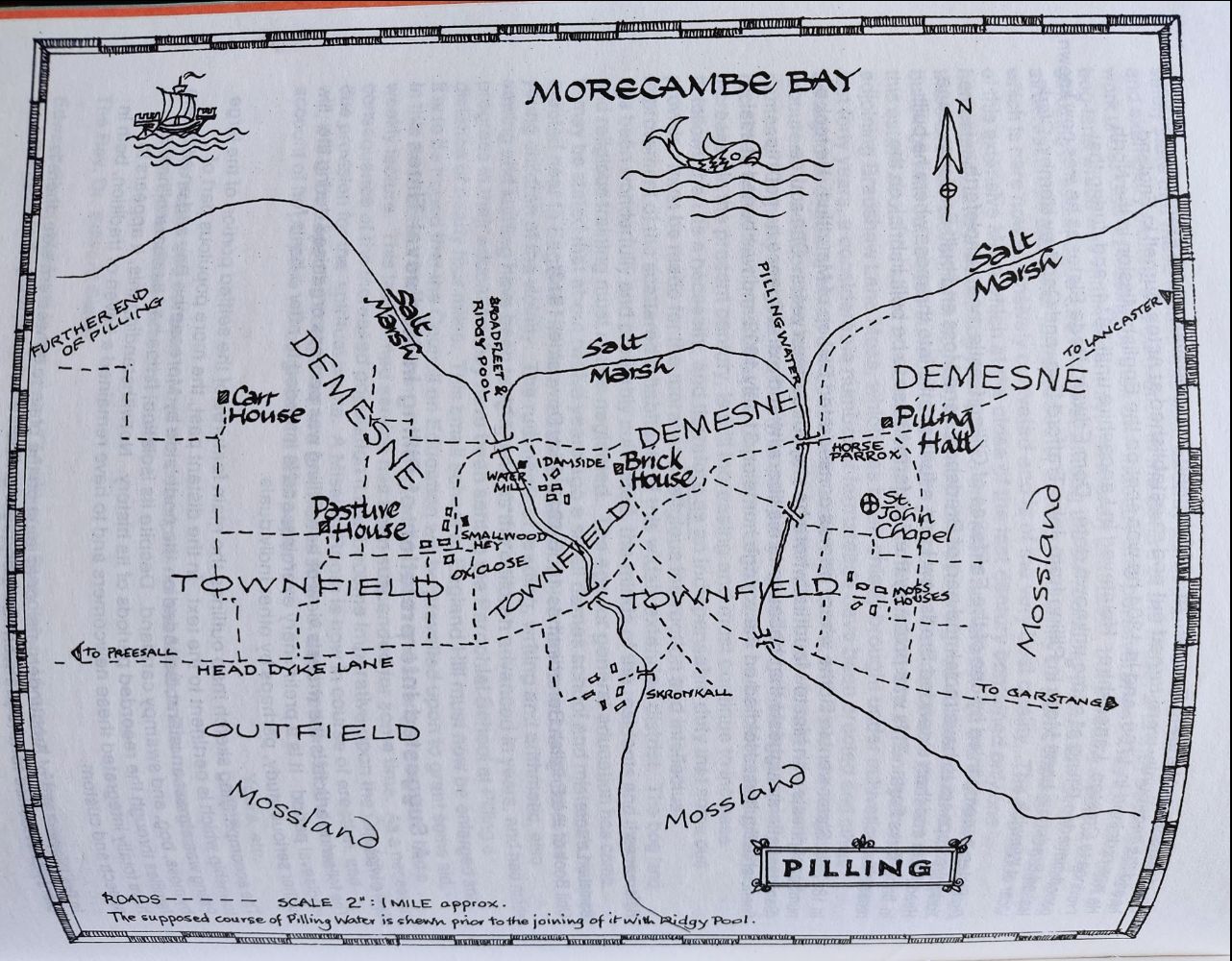

The accompanying sketch map outlines the main features of the settled portion of the large township which is pertinent to the text. In the distant past, the more populous part of Pilling was almost an island, bounded on the north side by Morecambe Bay and on all others by moss, bog, and swampy carr land. Despite its isolation, it has had its share of new families through the recorded periods of its history. Notwithstanding this, it appears to have totally integrated these newcomers and to have remained a haven of tradition, both in speech and custom.

In the Wapentake of Amounderness, or at least on the plain to its western side, there is plenty of evidence for the pre-Norman Conquest division of townships into administrative units called quarterlands or quarterfarms. An outstanding example is to be found at Woodplumpton, where the four hamlets of the township - Plumpton, Catforth, Eaves, and Bartle- were officially termed "quarter" until well into the eighteenth century.

It would appear that each quarterland had a principal house, the residence of a principal freeholder. In Piling we find four important residences in Carr House, Pasture House, Brick House, and Pilling Hall. All except Pasture House bear witness to a moated site in the first instance, and further investigation there may also turn up evidence of this kind.1

Under the control of each principal house was a hamlet wherein dwelt the bondsmen and also, if there were any, the smaller freeholders. In places comparable with the large township of Woodplumpton, each hamlet would have had its own field and pasture. In a township such as Pilling, with its large acreage of undrained moss, the circumstances dictated that there was only one arable area, customarily known as the townfield or Infield2. The writer tentatively suggests that the four ancient hamlets of Pilling were located at Smallwood Hey, Skronkall (Scronkey), Mosshouses and Damside. All of these are positioned on the perimeter of the area that the writer considers, mainly from the shape of the larger fields3, would have been the townfield. Some confirmation of this is suggested by two farms on the edge of the townfield area, which are known as Townside. One further indication is that a comparatively old farm, with a house probably dating from the seventeenth century, is located in the confines of the townfield and bears the name of Field House.

The mention of the infield and outfield refers to a system of agriculture which was practised in the North West and other areas of the Celtic fringe, contemporaneously with the more familiar three-field system of champion country, mainly found in the Midlands and South East4. The townfield (or infield) was divided into strips, and people held what they could afford. Cultivation was not controlled centrally by the court leet but husbanded as the occupant saw the need. It was not unusual for animals to be folded on the strips when they were fallowed. The outfield, which was divided from the infield by the headdyke4 supplemented the rather small townfields. Small closes in the outfield were cultivated in an "up and down" system; that is, turning the sward and cropping and fallowing for three or four years, to be returned to a rough leys for six or seven years5.

The above account refers only to the arable land that was mainly used for growing oats and barley for both man and beast. Apart from the obvious use of oats for porridge and clapbread6, bannocks and jannocks were baked and eaten on special occasions7. Minor crops were grown, such as wheat, pease, beans, rye, flax, hemp, bigg and vetches. One primary use of barley was for brewing.

Pasturage for animals would have been another major concern in the daily lives of the inhabitants of Pilling. As shewn on the accompanying map, there were two specific areas set aside for draught and riding animals, namely the ox-close and the horse parrox. General grazing for the few milch cows and fattening stock would be found in the outfield and, particularly in the case of sheep, on the fallow strips of the townfield, which thus served a dual purpose.

The only reference the writer has found to hay being made in Pilling is in the Cockersand Chartulary8, where a valuation of mowing grass was made in 1272 for the demesne lands. It names the Cellerars' Meadow (23 acres), Susterscale Meadow (44 acres), Chapel Meadow (near Pasture House), Court Meadow (near Carr House), and Moss Meadow, the last three totalling 31 acres. The total of 98 acres was in Lancashire or long acres and in statute measure would be approximately 160 acres. This calculation, of course, refers to the lord's land-in-hand. Lesser landholders must have made their hay in the outfield and occasionally from fallowed strips, left unploughed for that purpose.

Common land, or common of pasture, was normally most important in the economy of any manor. Pilling seemingly did not fare so well as most places, because at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, a survey made of Cockersands by the commissioners of King Henry VII in 1536, notes under the heading "Commons perteyning to the seyd house..... None but Pyllen Mosse beynge A foulle Marysse or Moore & percell of the Demean of Pillen & mete neither for comen of Pasture ne Turbarie ....."9.There is no mention of the village green or greens in the above survey. Part of Smallwood Hey is today known as the Green and is a rather insignificant triangle of land adjacent to the modern car park. The writer suggests that this is the remnant of a green that ran as a long strip past Village Farm towards the Golden Ball Hotel, and would have served Smallwood Hey.

With the demise of strip farming over the centuries after the fifteenth, many Acts of Parliament were passed to deal with the ensuing problems and local squabbles. In the North West, however, no such acts were necessary and people apparently made exchanges of land to their mutual satisfaction, consolidating their holdings into single units as close as was practical, and in all cases with the lord's consent. Common land usually required Parliamentary enforcement but as it did not affect Pilling, with its lack of commons, this area was immune.

Milling was done at Damside, and windmills are known to have been situated in the immediate vicinity since the late seventeenth century10. Damside also had a water mill, a much more ancient venue for the grinding of corn. The remains of this building are to be found in the base of the former outbuilding, converted recently to a house, and by the present early nineteenth century windmill11. Here, as in other manorial communities, a local rate was collected for the service rendered. We need not concern ourselves unduly with the tax burden of the mediaeval countryman, because the taxes he was compelled to find are with us still, under different names.

The lordship of Pilling had, from at least the thirteenth century, been vested in the abbots of Cockersand Abbey, and thus the cure of souls was provided from the Premonstratensian order. The old chapel site near to Newer's Wood is quite interesting. It consists of a low mound encircled by an oval ditch, in the manner of the foundations of the Celtic churches scattered over the western edge of Britain12. It is conceivably a much earlier Christian site than the abbey connection would suggest and may even have been a pagan site adapted by the early church.

By way of conclusion, it is often presumed that modern agriculture and civil progress in general sweep all traces of the past before them. Despite the modern onslaught, Pilling has, whether consciously or not, managed to preserve some tangible evidence of its feudal form. In practice, similar signs are to be found in most communities and much encouragement should be given to people to collate the facts before they become fainter. Not all manors were perhaps as lucky as Pilling, however, which had Boon Days well into living memory.

References

1. R Cunliffe Shaw, The Men of the North, Leyland Printing (n.d.), pp 185-90 et al.

2. See the O.S. map for Newton, near Whittington, in the Lune Valley. Clearly shown are two farms known as Infield and Outfield. Claughton-on-Brock also has an Infield House and a Longfield House in a quarter anciently known as Heigham.

3. Fields which are comparatively long in relation to their width, often with a slightly curving S-shaped boundary and occasionally a sharp step in the hedgeline may denote a divided strip. The curved boundary usually indicates the use of oxen in a long team, the length of which necessitated a sweeping approach from the headland followed by a similar exit.

4. HL Gray, English Field Systems, Harvard U.P. 1915.

5. A Eric Kerridge, The Agricultural Revolution, Augustus M Kelly, New York (1968).

6. Clap bread or oat cake; refer to Celia Fiennes' Journal, especially the reference to her stay at Garstang.

7. Bannocks were a flat, round, unleavened oat loaf and jannocks were a leavened oat loaf which also contained buttermilk or whey.

8. Cockersand Abbey Chartulary.

9. Ibid, quoting Duchy of Lancaster Rentals and Surveys 5.4, formerly classified as XXC G6.4 mems.

10. The Townley Map (c. 1680-90), Lancashire Record Office.

11. The wheel pit and one axle housing were observed, along with the traces of the mill race, by Hugh Sherdley and Richard Watson during recent alterations.

12. AH Allcroft, The Circle and the Cross. A study in continuity, 2 vols, Macmillan 1927 & 1930.