Parrox Hall, Preesall

by RC Watson and M E McClintock

At the time of the Domesday Survey in 1086, the 62 vills north of the River Ribble that were associated with Preston had no ploughlands or plough teams and there was population in only 16 of them. The rest of the area was waste, and it is unclear how far the Harrowing of the North in the years just before Domesday may have affected Amounderness and despoiled the local settlements (2).

The later development of the hundreds of Amounderness and Lonsdale South of the Sands were markedly different, however, and by the time of the 1664 Hearth Tax return (3), parish after parish in the Fylde is shown as having several houses with multiple hearths, while Lonsdale south of the sands numbered them only in single figures, with few exceptions. By the time of the Restoration, moreover, a number of the houses with which we are still familiar had been built, and previous articles in the Over-Wyre Historical Journal have documented some of these. On this occasion we wish to treat of a single house, Parrox Hall, partly because its development is sufficiently interesting to warrant more extended treatment and partly because our previous work has provided a convenient context into which Parrox now fits.

Parrox Hall is a long, low house set in parkland, and from a distance blends pleasantly into its surroundings, with its tall chimneys standing up well above the roofline. The pillars along the front façade and the whitewashed exterior are modern: its basic material is local handmade brick, with mullioned windows of brick plastered to represent stone. In this respect, as in so many others, Parrox has at least a cousinship with Liscoe (4), which lies only a few miles south-east as the crow flies.

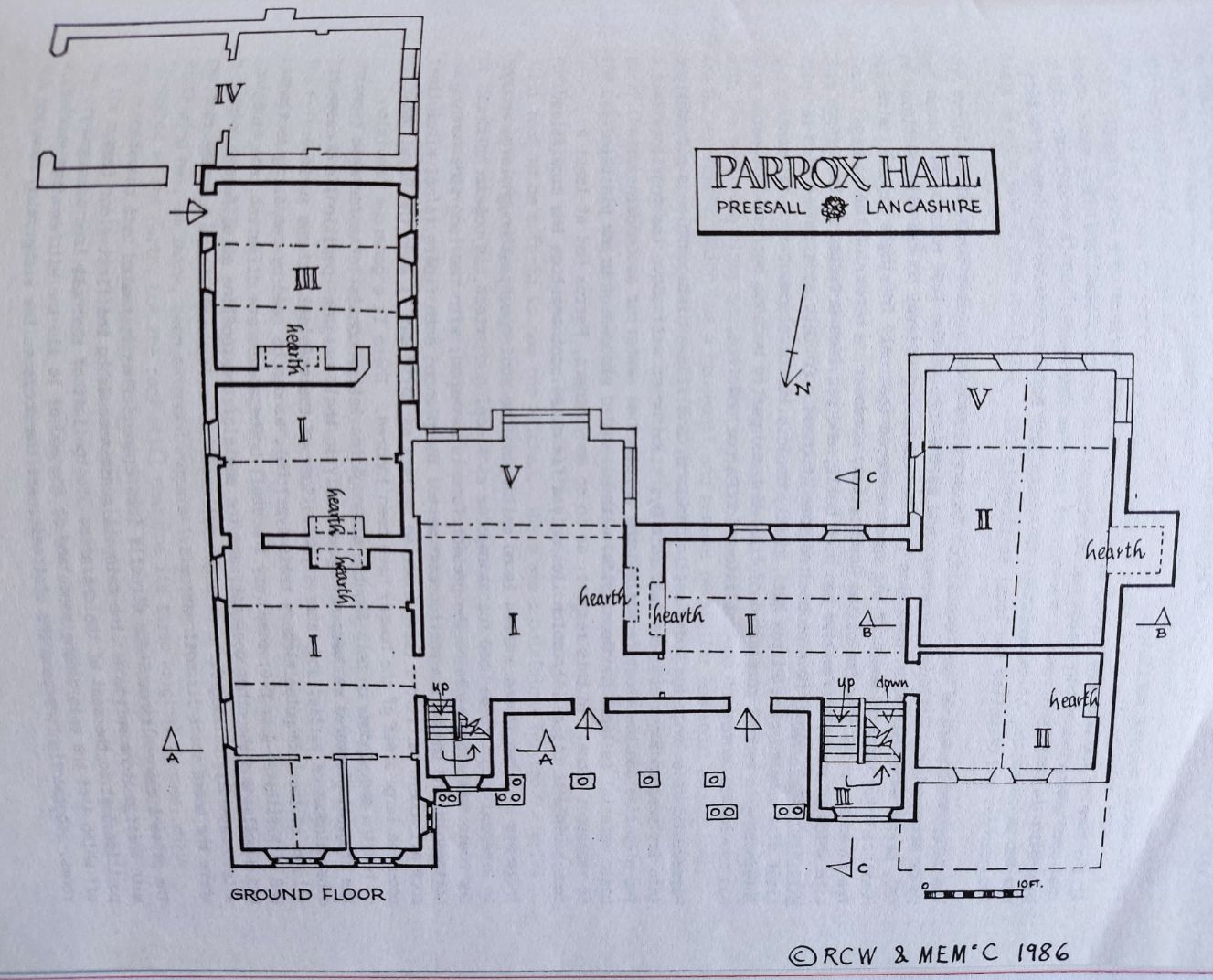

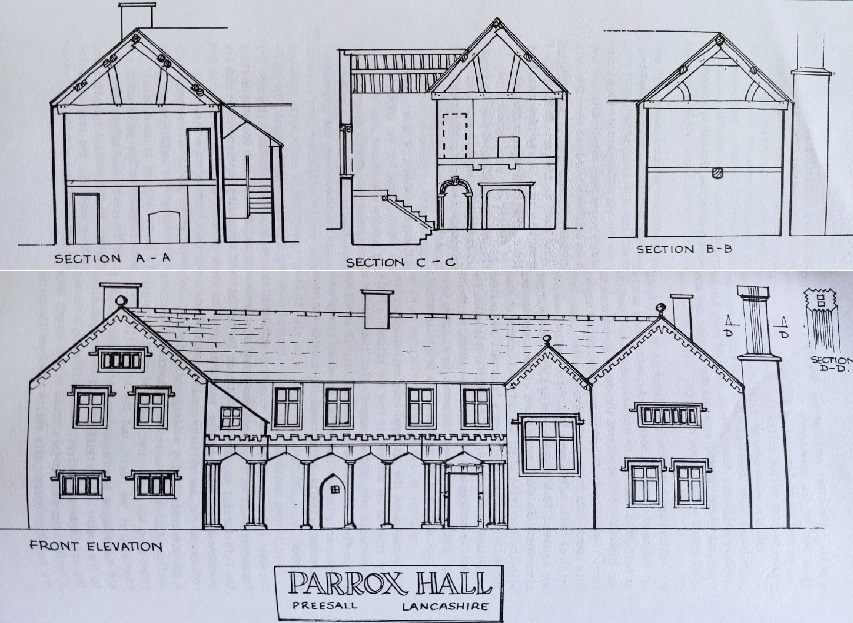

There are only two floors: there is no cellar and the roof space, although large enough in area and height to be used for storage or as sleeping quarters, is not now floored and has no staircase access. The present form is L-shaped, with the long side running north-south and the bottom section east-west. once all modern partitions (some inserted as late as World War II when the Royal Navy The plan on both floors is not dissimilar, occupied large areas of the house) have been ignored. There is a generous provision of hearths and windows on both floors, although the latter consist of three main types: the original plastered windows, not necessarily in their original position, and casement cross windows of earlier and later styles. Some of the original trusses survive: all are of the triangular tiebean truss type, but, as can be seen by comparing sections B-8 with either A-A or C-C, they vary in detail. The apexes are different, one type has a collar and the other does not, and the angle of the roofline at different points alters markedly, calling for a straighter, larger and more vertical strut on the roof where the house is at its most narrow.

The present main entrance leads directly into a panelled hall, heated by a hearth with a large stone surround: the main staircase ascends to the first floor from a position just to the west of the entrance. To the left of the hall is a passageway, off which lies the main dining room, and at the end of it lie the kitchens and service rooms. To the right, beyond the staircase, are the doors to the withdrawing room and a study. The older parts of the panelling in the hall belong stylistically to the first half of the seventeenth century and are extended in a reproduced form to complete the decoration of the rest of the hall: there are also vestiges of some early wallpaper behind several of the portraits. Beyond the service rooms are a later dining room and a library, also used as a sitting room, which have been created out of a former coach house. On the first floor there is a generous provision of chambers, on several slightly different floor levels, many of them furnished with very handsome four-posters. The first floor landing area and one chamber are also wood-panelled, including around their hearths and window openings.

The evolution of the house's plan form is not straight forward and we put forward what is set ut below as the best working hypothesis at present available. From the evidence we have had presented to us, it would appear that the earliest surviving structure was in origin T-shaped, and the original entrance is now the secondary door on the front façade, which has acquired a two-centred arched top at some more recent date. This opens into the space marked I on the plan, which we surmise could have been the original hall. This area has of course now been subdivided by a passage to the north, and extended to the south (see below). To the right (and west) is the present hall, also marked I, which we presume to have been the original parlour. We may draw parallels with the surviving older section of Liscoe, Out Rawcliffe, home of another member of the Butler family, which has a housepart and parlour of similar and equal proportions; and with Quaker's Farm, Out Rawcliffe (5), which in its last stage of development echoed a similar arrangement. A staircase which, by the thickness of the walls, appears to be of the same period as the rooms in 1, rises from this suggested original hall on the east side and was probably the original main staircase of the dwelling.

Further east of the proposed original hall lies one of two cross-wings, of which the first room to be entered is now the kitchen. There are subdivisions for two butteries at the north end, and we suggest that these three rooms and the one beyond also belong to the first stage (and are marked I). This kitchen area could have been a dining parlour and, before the butteries were formed, would have been of very generous proportions and well-lit. The remaining room to the south would thus have been the original kitchen.

The next major stage of the house's evolution occurred, from stylistic evidence, in the second half of the seventeenth century, and was presumably the responsibility of the Fyfe family, who had married into the Butler family and who lived at Woodacre in Barnacre (6). This addition took the form of a smaller cross-wing on the western side, containing two new parlours on the ground floor and two chambers above, as well as a gable turret housing a new grand staircase. This stairway, opening from the former parlour which now became the hall, culminates in a landing of its own. This second cross-wing has, we think, been extended comparatively recently at the south end and truncated at the north, but the roof still contains its three original trusses, which are numbered as the carpenters left them. Truss I is now embedded in the gable wall to the north: it is infilled and faced with a larger and later style of brick than the original narrow type, thus indicating a re-built gable. If there was originally a further bay beyond this truss of the length usual for this dwelling, the line of the original north gable wall would then lie on the same plane as the north façade of the original cross-wing of the T-shaped building. A particularly interesting feature of this newer cross-wing is the prominent, external chimney stack with its decorative, fluted and moulded brick work (see section D-D), that serves the present withdrawing room. This was probably one of a pair, and its companion was presumably lost when the removal of the north end of the wing became necessary.

The third and fourth stages of development may be considered together. At the southern end of the east wing is a room marked III on the plan and beyond it is a gable with a pointed, broad arch which was formerly a carriage room and an inner harness room, later incorporated into the house. The room marked III has beams which could belong to the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, and these sit directly in the wall rather than being seated on pilasters as are the other beams in this wing. Although the section marked IV has one of the older, mullioned windows on its upper floor, this is likely to be a reconstruction or a removal from elsewhere.

The windows and door types in other parts of the house have also passed through stages of change and renewal. Two square-cut cross windows are all that remain of an inter- mediary phase, but a more dominant type of window includes several that were originally inserted as early vertical sash windows and were later converted to casements. Concurrently with the introduction of these sash windows, probably in the mid eighteenth century, the internal doors at the western end of the house were updated to the fashion of the day. These have six fielded panels, the top pair of which have shouldered, semi-circular heads. Probably contemporary with these are the two archways, leading off the hall to the ground staircase and the dining area, which have semi-circular heads and a keyed architrave.

The final stage in the main development of the house are the areas marked as V when, at the turn of the twentieth century, the dining room and withdrawing room were extended to the south. Reproduction cross windows were placed in these extensions and many of the existing sash windows were treated in the same way. At the same time the early wooden hearth in the hall was replaced by one of stone, a change which was intended to lessen a fire hazard (7), and for the same reason an external portico at the north elevation was given stone pillars in place of timber.

If we look at the ownership of the house, the succession has not been unduly complex. There is mentioned in the Hearth Tax of 1664 (8) for Preesall a six-hearth group for which a Mrs Butler is liable, and since we know that Butlers had been living on and in possession of the site from at least 1586 (9), it is reasonable to make this identification. It also tallies well with our suppositions on structural grounds about the stage of development of the house at that date - ie a complex of four hearths (two at ground floor and two at first floor levels) between hall and dining areas in the centre of the main wing, and two at ground floor level in the east wing. We see from the same hearth tax that there were at Out Rawcliffe five families of Butlers, of whom one was an esquire and two were gentlemen, and all of whom had several chargeable hearths, including a Rich, Butler de Liscoe with four. At least two of the other named Butlers would presumably have been at Middle Rawcliffe Hall (now Rawcliffe Hall) and Lower Rawcliffe Hall (later Quaker's Farm, which previously stood at Town End).

A Butler daughter, Ellen, married in 1648 a William Fyfe of Wedacre (Woodacre) (10), who may be the same person as the Doctor Fyfe already mentioned and who boasted of seven hearths. William and Ellen had four children; Thomas, Richard, Mary and Catherine. The 1694 will for Thomas is extant (11), in which he left all his lands in Preesall and Hackensall, Poulton and Thistleton to his married sister Mary Bell and her children, with the proviso that if that line failed they were to go to his sister Catherine, wife of John Elletson, stated to be of Lancaster, gentleman, and through any sons of hers who are also the descendants of William Fyfe. In 1734 Catherine Elletson died as a widow at Coatwalls near Preesall (12), and left a will which mentioned no lands. It is evident that by this date the Bell line had indeed failed and that Catherine's son, William Elletson was installed at Parrox, where his descendants still reside (13).

We are therefore fortunate in having at Preesall a house which has been in the hands of a single family, who have lived in it as a single dwelling, for at least two and a half centuries. At times of prosperity they have added additional accommodation and reordered what they had, as suggested above for phases II to V, but the basic plan form has remained intact. We have obviously speculated about whether there could have been any earlier structures on the site before around 1600, but a date of this period does not conflict with the information that the Butlers came into possession of the land by at least the 1580s, and is also congruent with Liscoe. That too appears to date from the very beginning of the seventeenth century, but there the central core of the building remained essentially unchanged until modern times, except for the construction of a separate small cottage at the side of the main house. At Parrox, however, cross-wings were pushed out and then extended, and the result is the well- proportioned and handsome building that stands, in company with Hackensall Hall, almost within sight of the flat Wyre estuary.

References

1. Parrox Hall lies close to the mouth of the Wyre, at SD480 361.

2. (Ed.) H C Darby and I S Maxwell, The Domesday Geography of Northern England, (C.U.P., 1962), pp 67 and 392-418.

3. Public Record Office, E.179/250/11, Part II.

4. RC Watson and M E McClintock, "An Early Rawcliffe House and its Contemporaries" in The Over-Wyre Historical Journal II (1982-83), pp 7-13.

5. RC Watson and M E McClintock, Traditional Houses of the Fylde (University of Lancaster, CNWRS Occasional Paper 6, 1979), pp. 73-75.

6. Victoria County History of Lancashire, Vol. VI (1908) p 33.

7. Information supplied by Mr Harold Elletson of Parrox Hall.

8. Public Record Office, E179/250/11, Part II.

9. Victoria County History, op. cit., p 33.

10. Ibid.

11. Will of Thomas Fyfe Esq of Preesall in Hackensall, Richmond Wills R. 33, deposited at Preston Record Office; made 12 March 1694, proved 2 January 1695.

12. Will of Catherine Elletson, late of Lancaster, later of Preesall, widow, Richmond Wills R. 31, deposited at Preston Record Office; made 25 May 1734 and proved in the same year. Her husband's will, also mentioning no lands or property, is in the same bundle as hers.

13. We should like to record our warm gratitude to Mrs D H Elletson and her sons Harold and Chandos Elletson for their ready help and assistance at all stages of the work documented here.