The Preesall Salt Industry - Part 3 - 1912-1923

by Rosemary Hogarth

By 1911, brine and water were being pumped under the River Wyre from Preesall to the Fleetwood Salt Works for the production of table salt and common salt and to the Ammonia Soda Works for alkalis. Rock salt mined in Preesall was conveyed by the mineral railway to ships at Preesall jetty to be transported to Widnes for chemicals, the Continent for brine and Australia and South America for agriculture. A small amount of white salt was produced in Preesall (1). There were no great spoil heaps; There were no great spoil heaps; anything which could not be sold was put back into the mines.

On 23 August 1912, a 1 mile-long branch line was officially opened from the Knott End - Garstang railway to the Preesall Salt Works. The branch line had been constructed in 1911 and had already moved 208 tons of white salt and rock salt from the works and carried fuel and materials to the works. Two special trains ran between the mine and the Knott End - Garstang railway line each day and the timetables indicate that the salt trucks were dropped and picked up at the siding and did not go to the Knott End yard for marshalling.(2)

This direct link with the national rail network improved the situation of the rock ferriers who had previously worked on piece-work to meet the demand of the ships. When there were no ships due, the ferriers did casual labour on farms(3). Now they had full employment in the mines. In 1913, 5,032 tons of the 115,000 tons of salt mined were taken from the Preesall works by rail and 7,970 tons of fuel and materials were carried to the mines (4).

The bulk of the production was obviously still going out by ships. In 1914, only 3,058 tons of salt were taken out by rail and 5,926 tons of fuel and materials brought in (5). The tonnage of rock salt mined dropped to 100,000 in 1914 and 57,000 in 1915, picking up to 73,000 in 1916 (6).

In 1915, up to 500 tons of salt a week were going to Widnes for cell electrification of brine for chlorine gas, to counteract the German mustard gas (7). The number of people employed at Preesall increased to over 300. In 1915, 11,146 tons of white and rock salt left the works by rail and 9,928 tons of fuel and materials were brought in. In 1918, 30,914 tons of salt, less than half the salt mined, left the works and 7,880 tons of fuel and materials were brought in (8).

The Salt Works and Ammonia Soda Works at Thornton were requiring more brine and water, so further water wells were put down east of the Fault. On the advice of Mr Mansfield, a water diviner from Liverpool who used a magnetic instrument of his own invention, three wells Nos 43a, 44a and 45a were put down on Robert Cardwell and the Hon Mrs Lugley's land between 1915 and 1917. In 1919, No 46a was put down on Robert Cardwell's land (9). All these wells were put down to a depth of about 400 feet. They were very necessary because some of the wells in the Parrox and Klondyke yards had started throwing up sand. Because of the proximity of the Knott End - Garstang railway, line Nos 38 and 39 in the Patrox yard were closed and filled in, as was the 20 foot diameter, 6 foot deep hole which formed near No 38. In the Klondyke yard, No 40, which immediately adjoined Head Dyke Lane, was successfully repaired and continued production (10).

The Preesall water contained 38% of hardness and if unsoftened caused scale in the boilers. A small softening plant had been erected in 1908 at the mine for dealing with the water required by the Preesall boilers. Water delivered to the Ammonia Soda Works was treated at the Ammonia Soda Works before being used in their boilers. In 1912, an experimental permutit softening plant of 2 units capable of turning out 2,500 gallons of softened water per hour was erected at Preesall. This experimental plant was so successful that the softening plant at the Ammonia Soda Works was dismantled, the Preesall plant enlarged and all the Ammonia Soda Works' water requirements were softened at Preesall. Eight units (later increased to fifteen), were put down by United Water Softener Limited, successfully reducing the hardness to 5% (11). The Chief Chemist for United water Softener was Dr Bloch. According to W W Gleave, United Alkali Company's chemist at Preesall, Dr Bloch was a "typical stiff, cigar-smoking Prussian with duelling scars" who came monthly to Preesall until 4 August 1914, the day war was declared on Germany, when he disappeared. His firm later had a letter from him asking if they would look after his wife and children until he returned or they could leave the country. He was a prisoner of war in Paris, having been shot off his bike while leading a detachment in Northern France. He also asked for a small loan(12).

During the 1914-18 War, women increasingly took on the work above and below ground. Mrs Sarah Smith, then Sarah Dodgson, was born the tenth of eleven children at "Rose Cottage", Knott End. Four of her brothers worked at Preesall Salt works. Tom, who worked down the mine was killed on the Somme. Jack, who worked at the jetty loading ships with salt, was also killed in the 1914-18 war in Belgium. Between 1914 and 1918, Sarah Dodgson worked with six other girls in the top warehouse at the Salt Mine. They painted waggons, loaded them with salt and pushed them on a platform. They obviously enjoyed themselves although the work was hard and on one occasion got a "roasting" from their boss, Robert Breckell, for tipping over a wagon. Once, the salt pile they were loading had set so hard that they had to use picks and Sarah was told that the pile had not been disturbed since her brother Harry had worked on it many years earlier. The girls also had to dig a pipeline to a derrick, probably No 45a, near Head Dyke Lane.

They were taken to the site in a flat-bottomed cart owned by John Dickinson of Down Town. One day they found their pipeline blocked by a sheep. With much mirth, they pushed and pulled it out. Sarah Dodgson also worked in the stores, weighing nails and keeping check on everything that left the stores. She stopped work in 1919 to get married. Her wage had been 28 shillings per week. Just before she left, her nephew started work at the Mine. She had two brothers-in-law working there; John Edward Carter in the office and Jack Johnstone in the smithy (13). Her family are typical of the continuity of successive generations working for the United Alkali Company which goes on to this day in ICI.

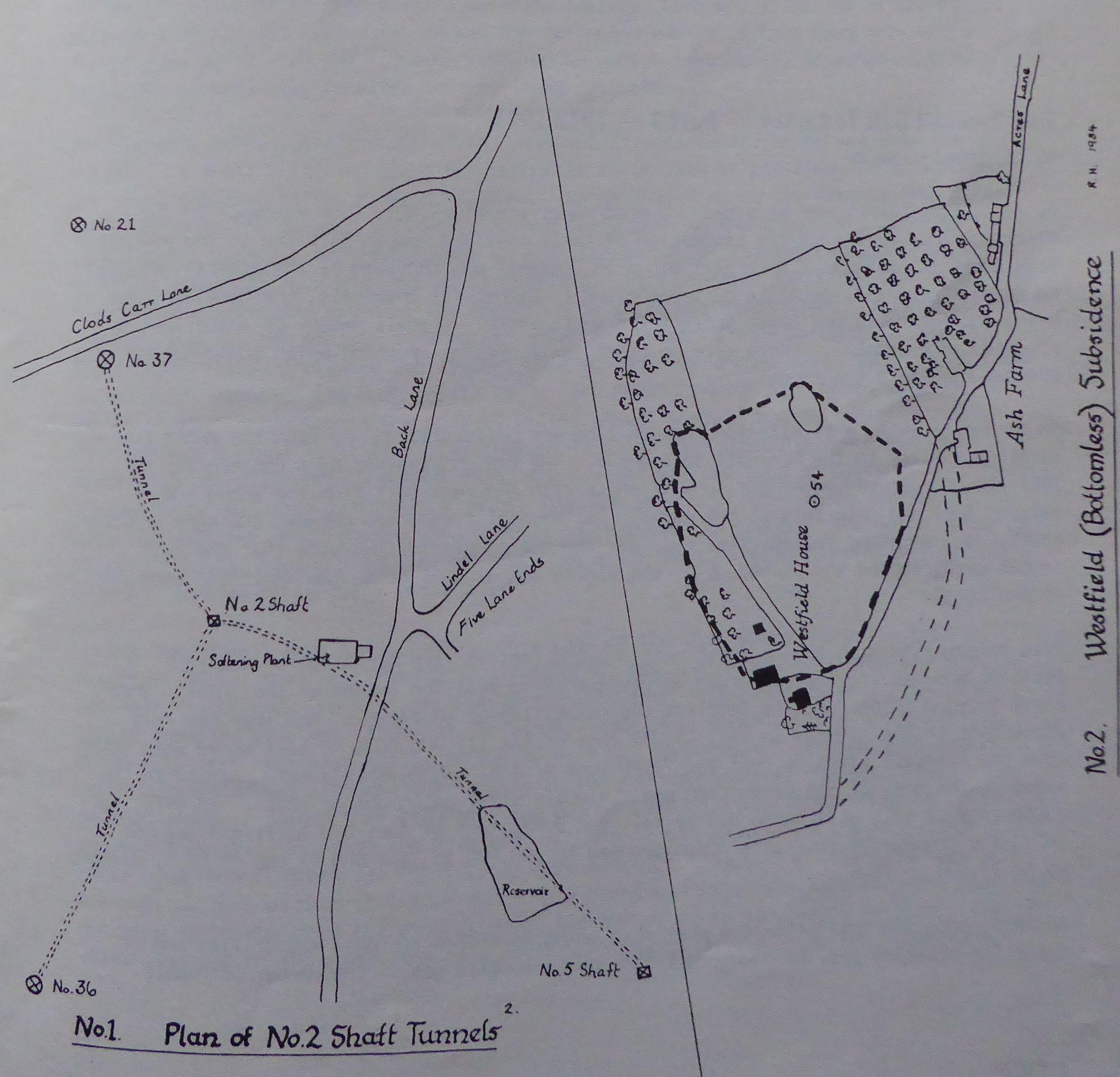

During the 1890s, considerable amounts of brine had been obtained by putting water down one brine well and allowing it to take its own course up through the rock salt to be pumped up another brine well. Although this method successfully improved the quality and quantity of the brine, it tended to cause subsidence. When the salt immediately under the rockhead is dissolved, the marls above are incapable of supporting the surface. The land round No 23 brine well, down which water had been put to supply No 2 shaft with brine, subsided to form Acre Pit (14). The land round No 21 down which water had been put also to supply No 2 shaft gradually subsided to form part of the Flash (15). Tunnels had been made for brine wells Nos 36 and 37 to supply No 2 shaft and through it No 5 shaft (see diagram 1). Owing to the proximity of the mine, No 36 was not used for this purpose after 1897. Shafts 2 and 5 were not used after 1911 but left in a state of equilibrium so that any brine or water pumped at No 5 would cause a flow of brine from No 2 and any brine pumped 16 from No 2 would cause a flow of water from No 5 (16).

In March 1919, brine was noticed to be dripping from the roof of the top mine. Water or brine in a salt mine is very dangerous. By April 1920, 7,000 to 8,000 gallons per hour were running through the roof (17). The brine was coming in from No 2 shaft causing a flow of water from No 5 shaft through the tunnel. The pumps were started without effect and the fear was that when the water flowing through the tunnel from No 5 shaft reached the rock salt portion of the tunnel, it would dissolve the rock salt upto the rockhead and cause subsidence. Immediately above the tunnel were the water-softening plant, water reservoir, public highway and numerous pipelines and railway sidings. It was decided to fill up No 5 shaft and the tunnel. This very difficult task was successfully completed in 1926 and will be described in "The Preesall Salt Industry", Part 4.

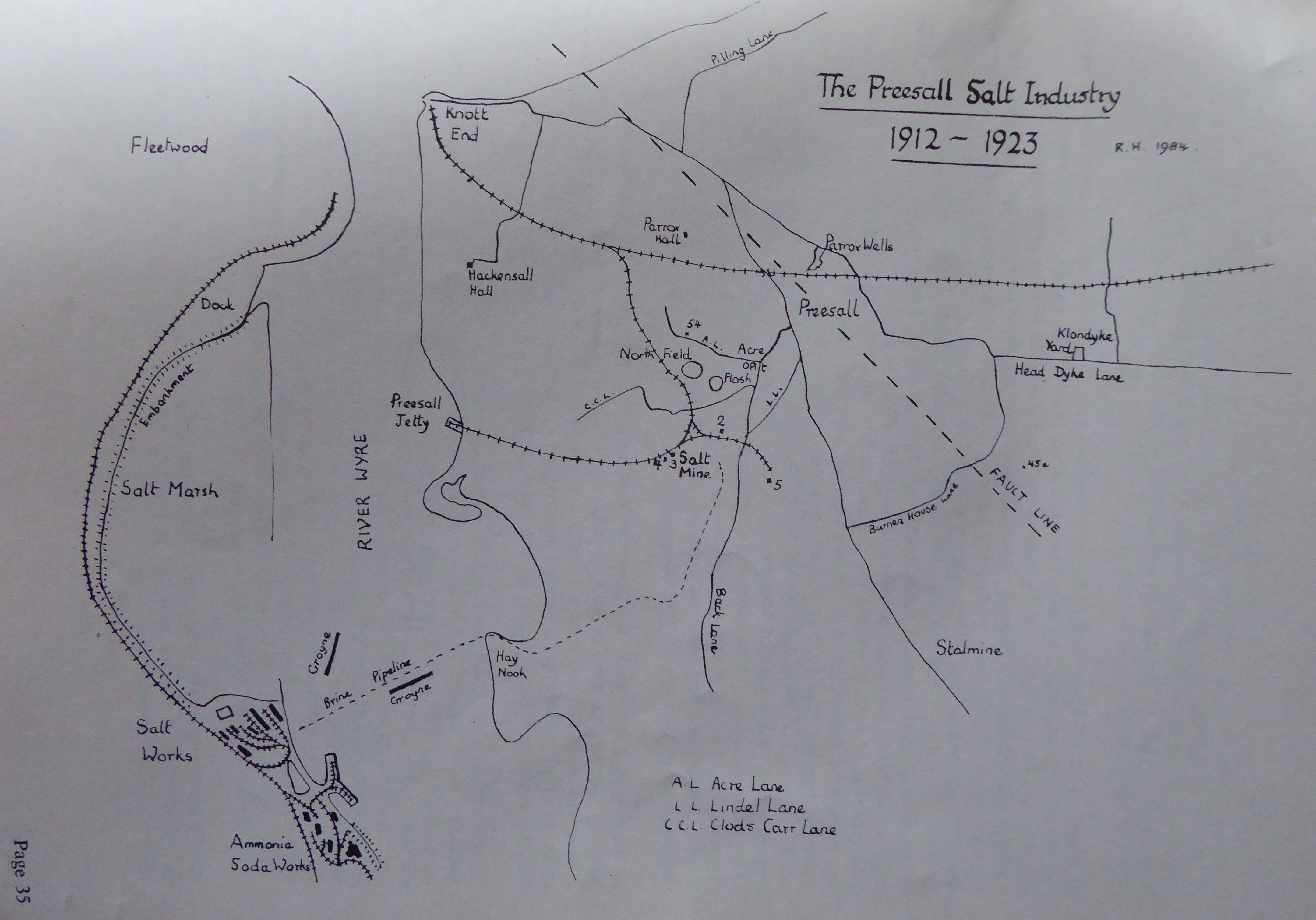

After the rockhead brine had begun to come into the top mine, it was noticed that a surface subsidence was spreading towards No 54 brine well (18). (See diagram 2.) This forced brine well had been put down in 1909 just east of Westfield Farm on Acres Lane. Early in 1922, the water pressure suddenly went off in No 54 and it was found that both lining and uptake tubes had broken off at the rockhead and the upper portions had shifted sideways. The well, which had yielded brine equivalent to 353,000 tons of salt, was abandoned. Mr F J Thompson ordered another well to be put next to No 54, installed an old-fashioned beam pump and told the men, "A gallon here is a gallon less in the mine" (19).

On 28 June 1923, workmen removing the disused derrick from No 54 noticed a slight depression in the ground. Jim Whiteside, who was driving a truck across the area, reversed it rapidly as the surface grass broke, revealing a hole about 12 feet in diameter (20). A week later, the hole was described in the "Fleetwood Chronicle" of Friday 6 July as "the subsidence may be likened to a wine glass, with a rim of 35 yards in diameter and about 60 feet deep, the stem being formed of a circular shaft of about 15 feet round running to a depth not known but probably extending to the brine cavity .. some 30 or 40 yards distant is a farmhouse and its outbuildings but as the fall of soil is from the direction of the disused well-shaft, no fear is entertained for the safety of the farm and buildings".

By August, part of Acres Lane had become unsafe, some farm buildings had been pulled down and the crater, according to the "Fleetwood Chronicle" of 10 August, was 60 yards in diameter and 60 feet deep. On 28 September, the "Fleetwood Chronicle" reported, "The huge subsidence which is causing so much interest in the Over Wyre district does not yet show any signs of ceasing. The cavity beneath is apparently as large as ever. The portion which has slipped in has left a space the shape of a funnel. The diameter across the top is about 120 yards. From the rim, the sides slope down steeply for a depth of 75 feet and converge on a small circular hole about 5 yards in diameter. Beneath this is a cavity, the depth of which is variously computed to be from 200 to 400 feet. Into this cavity have gone hundreds of tons of earth, the greater part of an orchard and several farm buildings". The "Fleetwood Chronicle" of 5 October devoted almost a page to the Westfield subsidence. Under the heading "Cavity that Roars", reported, "Intermittently, as you look at the great cavity ...... there come sounds as of the rushing of a subterranean cataract, then a rumble rising to the roar of thunder The roar has been heard at Pilling, four miles away .... This great hole, which is daily visited by hundreds of people from far and near, including many geologists, is of such a depth that it could swallow the Blackpool Tower and leave no trace of it". It is obvious why this subsidence is called "Bottomless" to this day in Preesall.

Mr William Hull and family who tenanted Westfield Farm were still farming and using the house by day but sleeping in an army hut in a field at a safe distance. However, on 7 November 1923, Mr Hull sold his cattle, pigs, farm implements and cheesing utensils prior to vacating the farm. Buyers were warned by the auctioneer that they would be unable to get cars and vehicles to the farm and advised to leave them in Preesall village.

The crater was roped round and day and night watchmen were on duty. It was still extending on 18 January 1924 when the "Fleetwood Chronicle" reported, "Last weekend there were alarming extensions to the great yawning crater wakened in the small hours of Sunday morning by bedsteads quivering beneath them Many persons were Far from showing any signs of becoming filled up, the hole seems to be getting bigger and people who previously thought that the subsidence held no terrors for their own property are now discussing the question of how far it will eventually extend. At night, brilliantly illuminated by huge white and red arc-lamps, the scene of the subsidence is an eerie spectacle. Coloured lights make the shiny sides crimson in appearance and the terrifying sounds of titanic earth combats which ascend from indeterminable depths' cause even the most hardy to step back hurriedly".

"Bottomless" eventually stabilised to the size shown in Diagram 2. Westfield Farm was pulled down and Acres Lane diverted as shown in the diagram. Like Acre Pit (21) and North Fields (22) it was a warning.

Meanwhile, during 1923, the first Knott End telephone exchange opened on 23 June (there were 17 subscribers and the United Alkali Company's number was 15); negotiations were begun by Preesall Urban District Council for the supply of electricity to the rest of the village by the United Alkali Company from No 5 Pumping Station; on 1 July the railway company were allowed to put up their tariffs leading to a strong dispute from the United Alkali Company (to be described in Part 4).

References

- Rosemary Hogarth, The Preesall Salt Industry, Part 2, 1892-1911 in the Over Wyre Historical Journal Vol 2.

- Information supplied by Messrs Neil Thompson and M Alvin Cook.

- Information supplied by Mr Harold Daniels, great-uncle of the writer.

- Thompson and Cook.

- Ibid.

- FJ Thompson, "An Account of the Salt Deposits at Preesall-Fleetwood and their Development". Unpublished, ICI 1927.

- Daniels.

- Thompson and Cook.

- FJ Thompson.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Information supplied by W W Gleave.

- Information supplied by Mrs Sarah Smith.

- R Hogarth and W Heapy, The Preesall Salt Industry Part 1, 1872-1891 in the Over Wyre Historical Journal Vol 1.

- Rosemary Hogarth, The Preesall Salt Industry Part 2, 1892-1911.

- F J Thompson.

- F J Thompson, "Notes on Forced Brine Wells, Preesall". Unpublished, ICI 1930.

- Ibid.

- Daniels.

- Ibid.

- R Hogarth and W Heapy, The Preesall Salt Industry Part 1, 1872-1891.

- Rosemary Hogarth, The Preesall Salt Industry Part 2, 1892-1911.