Cockerham Hall

by RC Watson and M E McClintock

The modern township of Cockerham, some ten miles from Lancaster and lying between the Lune and Wyre rivers, is a scattered community of hamlets and farmhouses. Near the rather isolated church is a low-lying farmstead, set back from the road, called Cockerham Hall. It is not mentioned in any local history, including Baines and the Victoria County History but proves to be a rare north Lancashire example of a late mediaeval hall and is therefore of considerable architectural and historical significance. A full survey of the building has now been undertaken and what follows is a report of that.

The hall stands within the former vill of Hillam, which belonged to Earl Tostig as part of his Halton estate until shortly before the Norman Conquest, by which time it had become part of the royal estate (1). In 1154 William de Lancaster I gave the whole of the manor of Cockerham to the Canons of the Abbey of Leicester: part of the land later formed the canonry of Cockerham and the rest was absorbed with part of Thurnham into the Cockersand Abbey holdings. The cell of the Abbey of St Mary in the Meadows was thus established in about 1207: there were difficulties in the confirmation of the grant of land, the new cell became conventual and its establishment did not rise above a maximum of four canons. In the middle of the fourteenth century the mother house at Leicester decided to put an end to the existence of the cell but the manor of Cockerham was held by the Abbey until the Dissolution of the Monasteries. No traces of the cell are now to be found.

The Calvert family however held the manor on lease from 1458 onwards and John Calverhead and his sons Thomas and William are recorded (2) as holding the whole manor, rectory and profits and were required to keep up the chancel of the church and the abbey's lodgings, as well as to provide at his own expense a week's food and lodging for one or two of the canons of Leicester and their servants when they visited Cockerham - an arrangement which provides further evidence of the scant development of the canonry. There is no mention of where the Calvert family lived but in 1400, during the wardenship of John de Forton, an extent was taken of the manor and church of Cockerham. In this tabulation are mentioned, amongst other possessions, a hall, with chambers, kitchen, grange, granaries, stable and ox-sheds, of which the total value was put at £117 7s 8d (3). A further clue to the standing of the family is given by Cunliffe Shaw, in an account of litigation in 1588 concerning the master forestship of Wyresdale and Quernmore in which he mentions that it involved a John Calvert, gentleman, of Cockerham Hall (4):he gives no source for this information but it is consistent with the family receiving a grant of arms in 1598. John Calvert died in 1618, leaving his son Richard, aged 20, as his son and heir. The family were recusant and suffered loss of property during the Commonwealth: they appear however to have been back in possession of the manor by 1718. The Nelson family of Old Hutton, Westmorland, acquired Cockerham Hall in the 1850s: the family live there to this day and in an earlier generation have even married back into the Calvert family once more. (5)

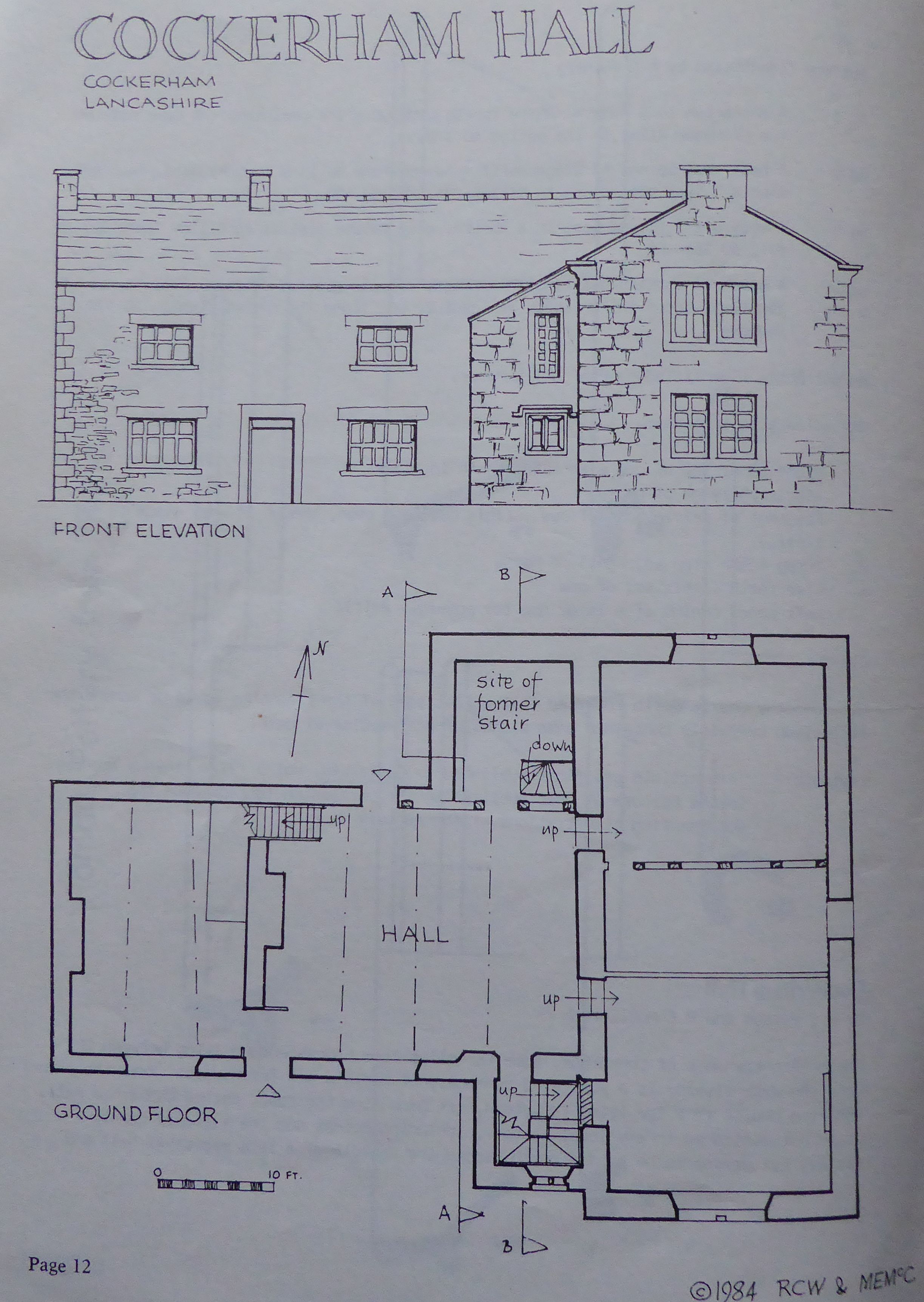

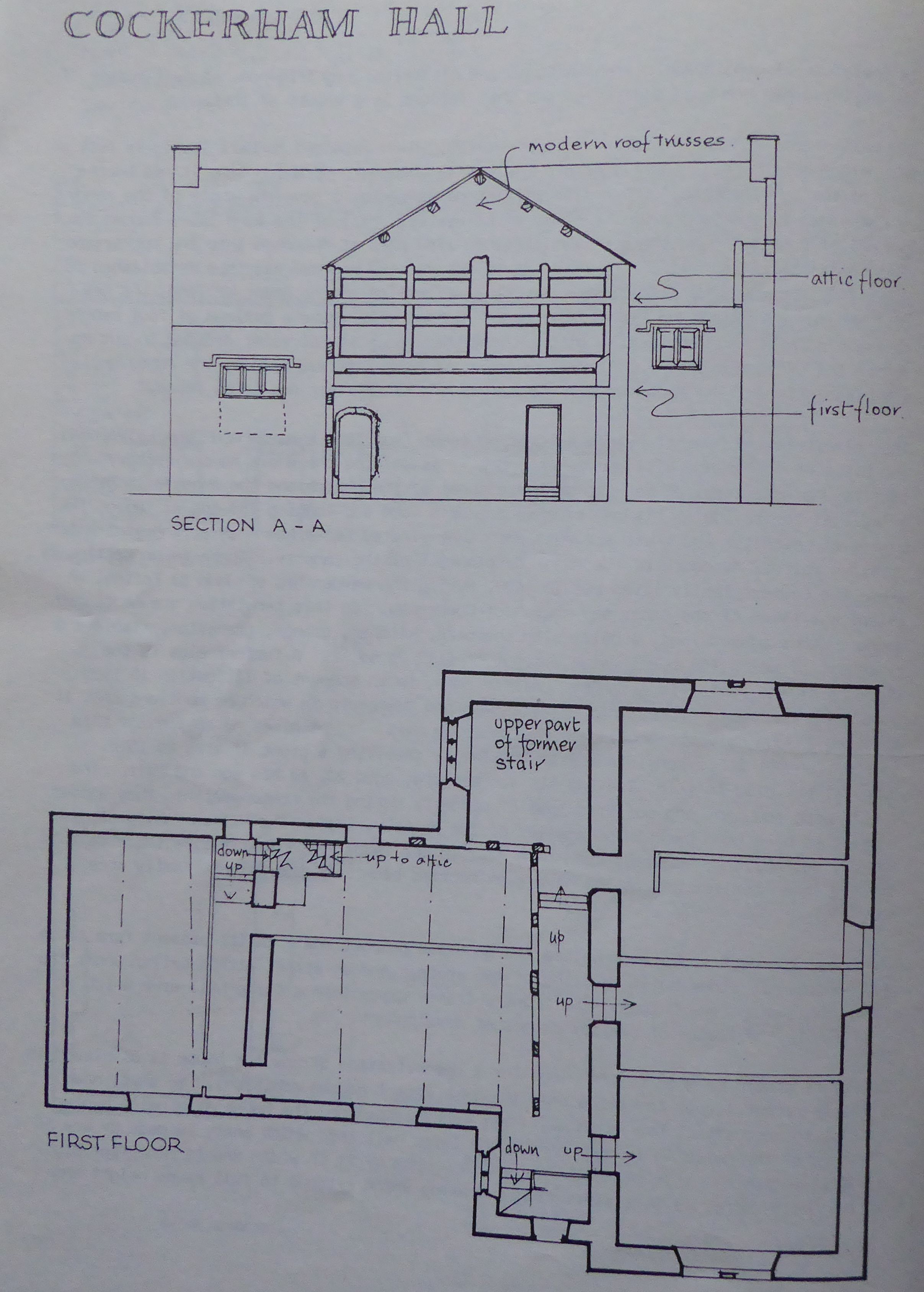

The house's modest appearance belies its generous proportions. In its present form it is a predominantly stone-built dwelling of two storeys and an attic, with a cellar under the later cross-wing (see below). The front entrance gives into a large hall area which at once displays evidence of earlier stages of development.

Reference should be made to the plans for a demonstration of how the house is displayed in a fairly recent layout (omitting only the most recent modern addition). We shall now attempt to reconstruct how we think, after much discussion, the house originally evolved. The core of the building is undoubtedly the large hall into which entry is made by way of a baffle entrance. This measures 25 feet in length by 21 in width and is nine feet high. In the north corner is some early timber framing which extends to full eaves height and on the adjacent wall is a stone doorway at the top of three stairs, leading into a later cross-wing. There is no certain evidence about the original date of the building and too little of the wooden frame is now extant to be categorical about the date of first construction. We are told that there was a fire before 1477 (6) in the manor house in which were burnt all the records of Cockerham up to that time and we suggest that the origin of the present building therefore relates to a rebuilding that took place after that fire.

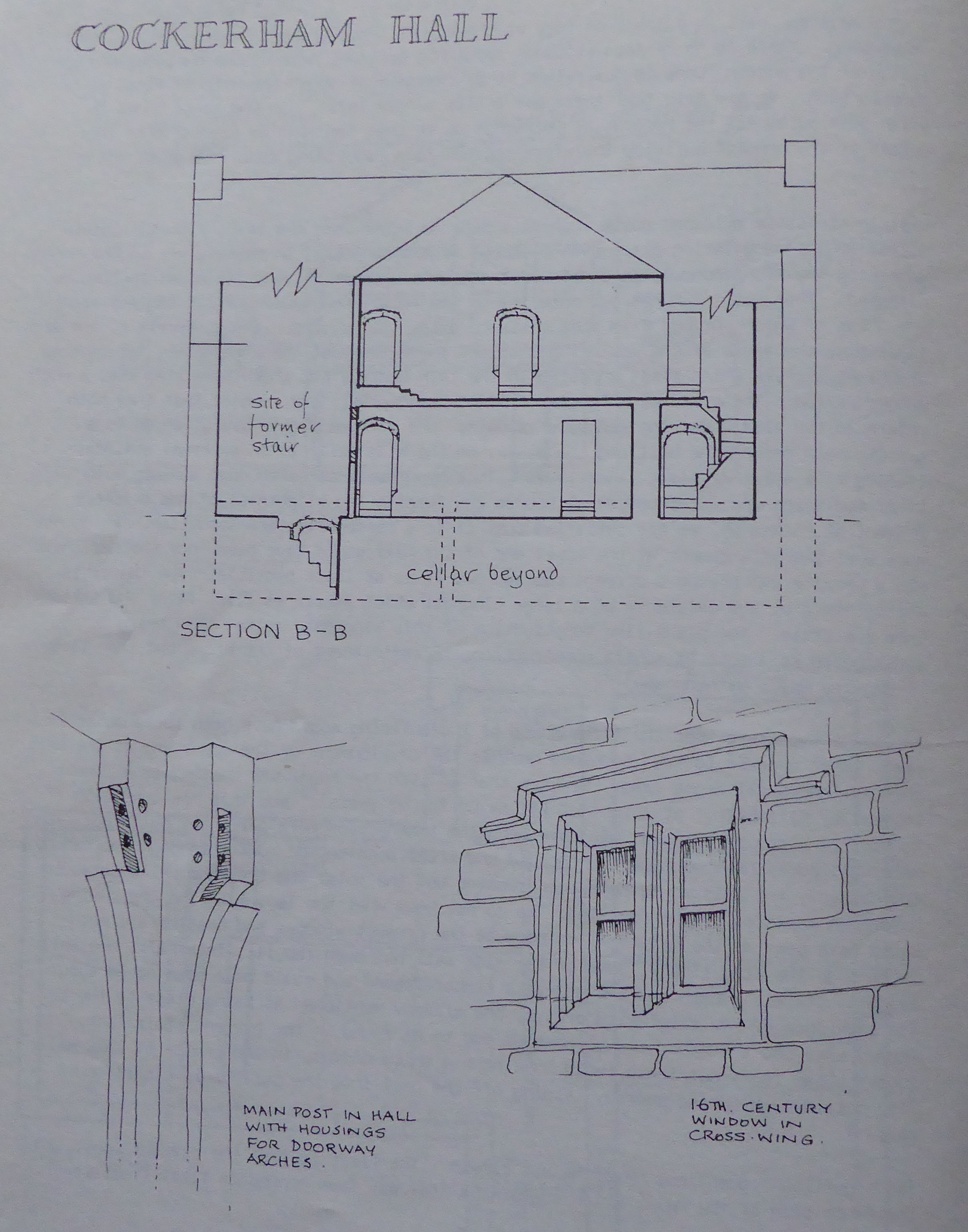

Certain stylistic evidence would support a date no later than the 1470s with the possibility of building taking place even a decade or two earlier. In particular, in the corner adjoining the stone doorway is a main post which is unusual in that its cross-section is L-shaped. This post also has cut into it, on two faces, the housing for a doorway arch, the shape of which springs from some distance below the housing. The steepness of the arch implied by the angle of the springing shoulder indicates that there were two, two-centred arches of a style which first appeared in the 14th century but which persisted over a much longer period. These are at an angle of 90° to each other: we suggest that they both relate to the area under the canopy of a dais; one of them might have given on to a private room beyond the hall and the other, on the side wall, to an external staircase leading to a solar at first floor level. This hypothesis is based upon analogy with other mediaeval and later mediaeval houses and despite the slightness of the evidence present at Cockerham, we are satisfied that it is a reasonable reconstruction. We do not know what the arrangement at the lower end of the hall would have been, nor whether there was a service end beyond a screens passage but it is at least possible. The theory is strengthened by the existence of a large kingpost which starts at first floor and extends into the attic. The plank-like construction of this kingpost, rather than being constructed as a post of square construction, is reminiscent of the broad but thin timbers of Baguley Hall, Wythenshawe (7).

We assume therefore that the first phase of the building would have been rectangular in plan. What appears to have happened next is the development of the upper end of the hall into a stone-built cross-wing. We know that in 1560 the manor was demised to a Thomas Calvert by Elizabeth I at a rent of £51 6s 0d for 90 years (8) and this new condition of tenure, in place of a lease, may have been the impetus for more permanent building. The main hall could have been left untouched and still open to the roof, although the canopy and possibly the dais would have been removed but the solar and the room below it would have been replaced by the new wing. We do not know what the layout of the cross-wing would have been at the ground floor because the present windows and hearths are much later than the wing itself, some of the side wall has been rebuilt, internally one wall is comparatively modern and the other is timber-framed and could have been moved about. The existence of the original doorways, one already mentioned as being close to the L- shaped post and the other now blocked up and to be found in the present stair lobby, suggests two rooms but there could have been a third doorway in the centre of this wall. (The cut-through second doorway leading off the hall into the parlour is clearly much later.)

Two significant questions nevertheless remain. The first is that the present lobby, on the south side of the hall, which contains a stairway from ground to first floor level, appears by the evidence of its mullioned window, external dripmould and thickness of wall to relate to the cross-wing but its purpose is far from clear and at present we can only suggest that it provided an ante-chamber for one of the new parlours. The other question relates to the northern corner of the hall where, beside the timber-framed doorway already described, is a further timber-framed doorway which has been inserted within the existing, wooden framework. It is the timber-framing above this door, which extends to eaves level in the attic, that has a slightly cambered head and can be traced through the intermediate floor. This doorway, until very recently, gave on to an area which had been used as a pantry which also contained a flight of semi-circular stone stairs leading to the spacious two-roomed cellar. The first of the cellar rooms is stone-flagged and has on its northern wall a partially blocked window of three narrow lights with double cavetto mullions. The inner cellar has an earth floor and a modern window in an old opening. The timbers used for the ceiling of this inner room, which are likely to have been borrowed from elsewhere in the house are very fine in their construction and moulding and are reminiscent of those to be seen on the ceiling of the ground floor of Barton Hall, near Preston, which is itself thought to be of a similar date. The pantry has in its most recent form a storeroom above which contains the upper part of a three-light mullioned window, again with cavetto moulding. The position of this window, in relation to the dripmould outside, would be consistent with its being a half-landing window for a grander staircase, which would have given access to the first floor corridor created above the open hall.

At first floor level the cross-wing allowed provision for new chambers but we again do not know exactly how many there were, since only two matching contemporary doorways remain in position: a third doorway could have existed above the blocked doorway below: the present third doorway, to the south, is clearly later than the other two. There is some attic space above the cross-wing but it is not now accessible and it is not certain whether it was ever used for either living or storage space.

The third phase of building was in stone and involved changes to the cross-wing, the rebuilding and ceiling of the hall and the building or rebuilding of a service wing to the west and this we suggest took place in the early nineteenth century. The service wing remains separate from the rest of the house and shows evidence in the first floor room and attic of having been used for heavy storage, possibly of grain. One interesting detail is the signs of chafing on a tiebeam in the service room attic which is just above a large trap door. It is probable that as part of this reconstruction the grand stair- case was removed from the present pantry and the stairs placed instead in what had previously been the ante-chamber. The stairs at the lower end of the hall were probably constructed at the same period.

Thus we suggest that in Cockerham Hall we have the remains of an extensive timber-framed hall house, with a later stone cross-wing and a nineteenth century remodelling. Elsewhere in the country, including Cheshire and south Lancashire, buildings of this type are more frequently to be found: as far north as Cockerham however they are far less frequent and their survival even more unlikely. We are fortunate that so much of Cockerham Hall's original structure has survived that it has been possible to postulate the reconstruction of its development given above.

References

- Victoria History of the County of Lancaster, Vol VIII (1914), p 95.

- Ibid., p 94.

- E Baines, History of Lancashire (ed. Harland 1870), Vol II, p 587.

- R Cunliffe Shaw, The Royal Forest of Lancaster (Preston 1956), p 201.

- Information supplied by Mr and Mrs George Nelson, to whom we are greatly indebted for their generous help and assistance.

- VCH, Vol VIII, op. cit., p 93; VCH, Vol II (1908), p 152. Reference is made to Bodl. Lib. MS Laud, Misc .625 (olim H.72), Fol. 45-526, 1676.

- JT Smith and C F Stell, "Baguley Hall: the survival of Pre-Conquest building traditions in the fourteenth century", Antiquaries Journal, Vol 40 (1960), pp 131-151.

- VCH, Vol VIII, op. cit., p 94.