The Pilling "Graves"

by Hugh Sherdley

In early July 1970, an agricultural contractor, Mr W Roskell, was working with a bull- dozer in a field belonging to Mr Arthur Holden, Beech House, Pilling (N.G.R.SD387493). Mr Holden, a poultry farmer on a large scale, had engaged the contractor to remove the top soil in part of a field and pile it up to form banks enclosing a rectangular area of ground, thus making a tank or 'lagoon' about an acre in size. This tank was to be used for the reception and storage of large quantities of poultry manure which would be pumped in.

When Mr Roskell had removed the top soil to below normal cultivation depth, the subsoil was revealed; this was a yellowish, fine-grained alluvial silt and on the exposed surface there appeared a number of dark grey, almost black, rectangular patches about 6 feet long and 2 feet wide and arranged in rows. Being curious, Mr Roskell dug out one of these rectangles with a spade and discovered that it was about 4 feet deep and filled with a dark grey material which was similar to the surrounding subsoil in texture.

The discovery of these "graves" - for this is what they appeared to be - was reported to the Lancaster City Museum and to Mr B J N Edwards, the Lancashire County Archaeologist, and with the co-operation of Mr Holden, who suspended work on the 'lagoon', the Pilling Historical Society were able to conduct an extensive examination of the site and excavate 20 of the "graves".

The excavation was planned and supervised by Mr John McNeal Dodgson of London University who had considerable experience of excavating Anglo-Saxon burial sites. Mr Dodgson, who is a native of Preesall, was on holiday at the time and his supervision was much appreciated.

Mr B J N Edwards, who was engaged on another important archaeological project at the time, visited the site from time to time with useful help and advice.

The site was also visited by Mr P L Drewett of the Inspectorate of Ancient Monuments who commended the way the excavation was being carried out and expressed a tentative sugges- tion that it might be an Anglo-Saxon cemetery. (This was subsequently thought to be unlikely.)

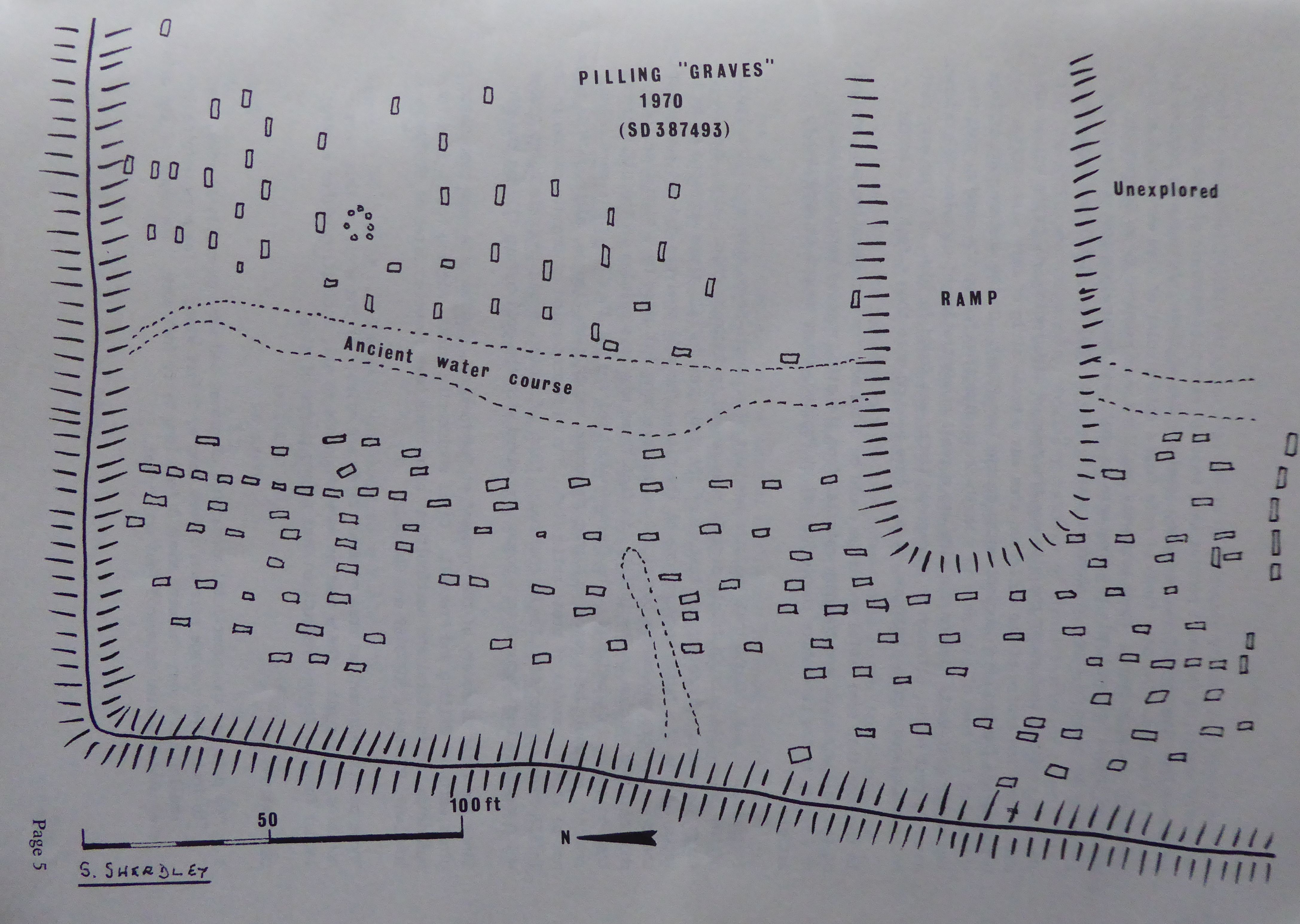

The whole area to be examined was marked out with a grid of 40 feet squares to enable each "grave" to be accurately plotted on a plan. (A reduced copy accompanies this article.)

Actual excavation of the pits proved very difficult until a standard procedure was adopted. A trench about 3 feet deep was dug in the soil outside and at each end of the pit to be examined; an excavator stood in each trench and very carefully sliced off the grey material with a sharp spade, taking off a 1/4 inch with each slice; a trowel was used where careful detail was required. Of a total of 185 pits on the site, about 30 were emptied, some of them unfortunately by inexperienced members of the public.

Pilling Historical Society excavated 20 of the pits using the slicing technique. Finds were very scanty, a few small pebbles were found in each pit. Possibly of some significance was the discovery of at least one, sometimes two or three, white quartz pebbles in each pit examined. The only finds of note from a dating point of view were about a dozen sherds of coarse pottery. These were very small and were examined by Mr Edwards who assigned them a medieval date but they were so small and featureless that a close date could not be given to them. A probable date between AD 1200 and AD 1500 was suggested.

The most striking feature of the site was the rows of dark rectangles in the yellow sub- soil. Down the centre of the bulldozed area was a broad strip of dark silt, this probably was the bed of an ancient water course (see Plan). On the western side of this stream bed the rows of pits were in a North-South direction but on the eastern side they lay mostly East-West. Also on the side was a small concentration of circular dark patches, possibly post holes, although no decomposed timber was found in them. If they were post holes associated with a structure, it must have been no more than 6 feet in diameter.

In the hope that some useful knowledge could be obtained from a comparative soil analysis of the yellow subsoil and the dark material from the pits, samples were submitted by Mr Edwards to the Lancashire County Analyst at Preston, whose report is appended to this article.

Initially, it was thought that the site was part of an Anglo-Saxon cemetery: the layout of the grave-like pits in fairly orderly rows seemed to indicate this. Also, due to slight variations in colour and texture of the dark grey infill, there appeared to be the vague outline of a human body in some of the pits. The soil analysis did not support this theory. If there had been a burial, it would have been indicated by a high level of phosphate and calcium in the infill: in fact there was less calcium in the pit contents than in the undisturbed soil. The County Analyst pointed out that "if there were animal remains, one would have expected higher phosphate and calcium figures, although this might not be true of remains of great antiquity". The high proportion of organic carbon in the infill could be accounted for by charcoal; this, of course, would indicate burnt timber which may have been reduced to a powder and mixed with the soil before filling the pit.

Since the first discovery of the "graves" at Beech House, similar pits have been noted in other parts of Pilling and Preesall. Civil engineering works, digging foundations for buildings, agricultural and horticultural operations have revealed sites at SD379487, SD401483, SD374484, SD373489 and SD413482.

These points represent an area of about 2 square miles; if the whole of this area contains similar pits, there must be many thousands in all, indicating either a large labour force or their construction over a long period of time.

Observations

- The pits had the superficial appearance of graves and were generally in rows, head to foot. The average size was 6 feet long by 2 feet wide; a few were marginally smaller and a very few were about 3 feet long by 1 feet wide. The depth of the pits excavated varied between 3 feet and 7 feet.

- The infill was of a different colour than the surrounding soil, the texture the same.

- Artefacts in the infill were very scanty, a few pebbles, mostly granite, one of two pieces of unworked flint and in every pit examined one, two or three pebbles of white quartz and a few very small pieces of coarse pottery in one or two of the pits.

- The infill was homogeneous, showing no evidence of stratification or clods. This could indicate that it was a liquid or semi-liquid mixture which was put into the hole.

- There was no sign of weathering on the edges of the pits. They must have been filled in very soon after being dug.

- Some of the pits showed evidence of having been lined with wickerwork or reeds or rushes. A few had decomposed grass in the bottom.

- With a few exceptions, the silted bed of an ancient water course running North- South down the site represented a division between pits aligned North-South and those East-West.

- There was evidence that some of the pits had had a capping of clay, which had been destroyed in the past by ploughing and cultivation.

In view of the almost complete lack of material which would give some indication of the purpose and age of the pits, it is impossible to express an opinion on their function. Suggestions as to their purpose have included graves, either human or animal, fish to flax retting pits, mediaeval slit trenches for defensive purposes, pits or troughs use for the manufacture of salt by the evaporation of sea water, storage pits of some kind rubbish disposal pits connected with some ancient industry and prehistoric graves in which human remains had been buried after cremation with wood, the resulting ashes and charcoal being reduced to a powder and mixed with water and poured into the grave. In view of the large number of "graves", it could have been a tribal burial place.

The available evidence does not give much support to any of these speculations. The hope is that sometime in the future a pit will be found which will answer all the questions.

In the meantime, it will remain the "Pilling Enigma".

Appendix

Report on analysis of two samples of soil received on 8 July 1970.

| M106 | M107 | |

| Pilling site | Pilling site | |

| Unstained soil | Stained soil | |

| Weight | 26 ounces | 30 ounces |

| pH | 7.2 | 6.8 |

The air-dried soils gave the following results on chemical analysis:-

| per cent | per cent | |

| Total nitrogen (as N) | 0.024 | 0.092 |

| Loss at 100 deg C | 0.75 | 1.84 |

| Further loss at 600 deg C | 1.38 | 2.83 |

| Phosphate (as P2O5) | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| Calcium (as Ca) | 0.15 | 0.11 |

| Iron (expressed as Fe2O3) | 3.08 | 1 |

| Organic Carbon | 0.235 | 1.02 |

| (equivalent organic matter in soil) | 0.405 | 1.72 |

Observations

Both samples were picked over, under high magnification, and the only differences noted were the presence of concretions of iron in the lighter soil and small fragments of very decayed wood in the darker soil. No bone fragments were present. From the chemical results, it may be inferred that the difference in colour stems from two factors. The first is the presence of the extra carbon in the darker soil and the second is the presence of a greater quantity of oxidised iron in the lighter soil. The slight acidity and the reducing conditions in an area of soil where decay was taking place could result in a leaching out of iron and the concretions of iron oxide found in the lighter soil suggest that this is what has happened.

If the organic matter in the darker soil had been caused by animal remains, one would have expected higher phosphate and calcium figures, although this might not be true of remains of great antiquity.

Both samples contained grass roots which suggests that they came from near the surface. If this conclusion is correct, then it is unlikely that even a more sophisticated technique of examination such as Radiocarbon Dating would prove to be of much value since in topsoil the interchange of carbon with the biosphere - ie from roots and decaying superficial organic matter, is likely to be recent and greater than the carbon left by ancient remains. On balance however the probability is that the stained area results from something entirely vegetable, such as a rotting tree stump, measurable in decades rather than hundreds of years. For Radiocarbon Dating confirmation deeper samples would be needed and it could probably only be done by the British Museum Laboratories.

A C Bushnell, County Analyst