An Early Rawcliffe House and its Contemporaries

by RC Watson and M E McClintock

Relatively close to the mouth of the River Wyre and along both its banks we find, within the span of a few miles, a set of idiosyncratic landed family houses which, although of vernacular construction, fall in design between the traditional Fylde house (1) and the few great houses of sub-mediaeval construction in the area. The great houses in question are Rawcliffe Hall, basically a timber-framed courtyard house; White Hall, formerly called Upper Rawcliffe Hall, witch despite extensive rebuilding in the 1850s has a basic mediaeval plan; and Nateby Hall, now demolished, which retained within its seventeenth century brickwork the evidence of earlier timber- framed structure and, again, an early plan form, consisting of central hall with crosswings.

The entire group of six houses with which we deal appears to have been built, from stylistic evidence, in the second quarter of the seventeenth century. The only tangible places of evidence however are a rebuilt doorhead lintel of 1627 at Bowers House, Nateby and a datestone at Hackensall Hall of 1656, just beyond our period.

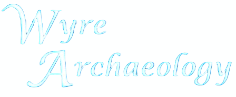

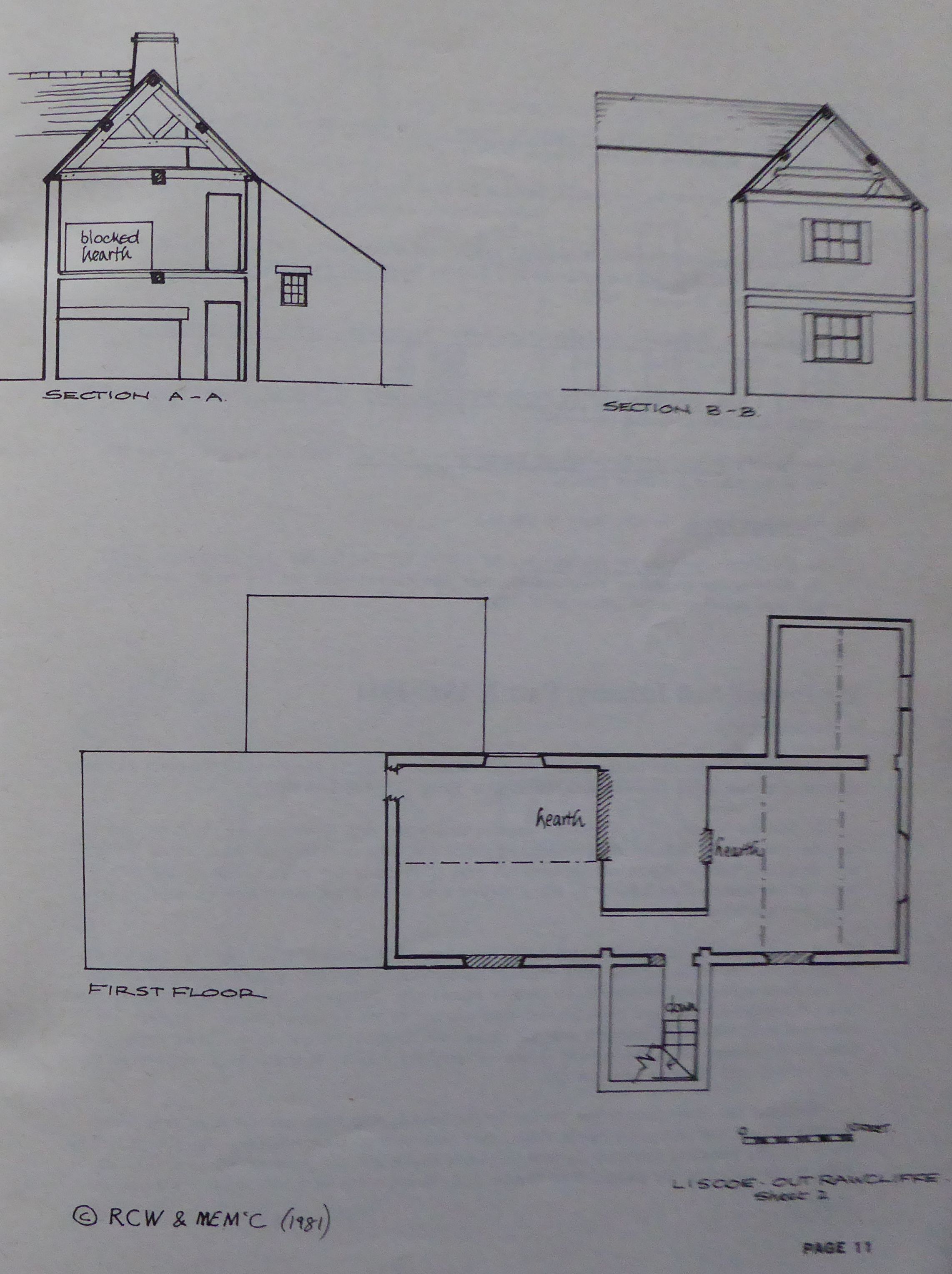

The outstanding example is a house and estate called Liscoe (2) at Out Rawcliffe, which stands on a small hillock just above Shard Bridge. The core of this large, rambling but handsome dwelling is a two-unit lobby entrance building, constructed of handmade red brick and with a small rear wing projecting to the east, making the original plan L-shaped. If we ignore the later additions of various dates at the north and west, which are shown on the plan, the main interest of the house is in its two-unit core. The ground floor was divided into a housepart to the south, with a small service room at right angles to it, and a parlour of generous dimensions with two six-light mullioned windows spanning the width of the north gable. The housepart has, besides a now bricked-up open hearth, one transverse beam with run-out stops. The beam in the service room is similarly adorned.

The parlour still retains its open hearth, which shares a common stack with the housepart hearth, and has a bressumer with Upper Wern Hir stops. Standing inside this, one can see the internal structure of the entire brick hood, to the daylight above. The hearth was lit on the east wall by a one-light window and on the west side the jamb was pierced by a small opening, presumably to act as a watching position for the original front entrance. The one central beam runs longitudinally and its simple chamfer terminates in a shield-shaped stop. During recent renovations the walls were stripped down and the remains of what was presumably the original decoration came to light. Over the bressumer were the fragmentary remains of some lettering painted in black on white plaster; unfortunately too slight in extent to decipher. Around the rest of the walls and particularly on the east wall, were the remains of a formalized fruit and foliage patterning in a blue-on-white design. At the same time, the remains of the former six-light mullioned windows were refurbished as a decorative feature: when first uncovered these tall, narrow lights, which are of splayed and mitred design and measure 2’ 3” by 8" still retained much of their covering of plaster, put as a coating over the brick and intended (as elsewhere, such as at Sowerby) to represent stonework. The common rafters of the ceiling were obviously designed to be on show and the room was completed by a handsome flagged floor. Despite extensive searching, it did not prove possible to establish the whereabouts or form of the stairs for the original two-unit house, although they were, given the overall proportions of the house, unlikely to have been insignificant.

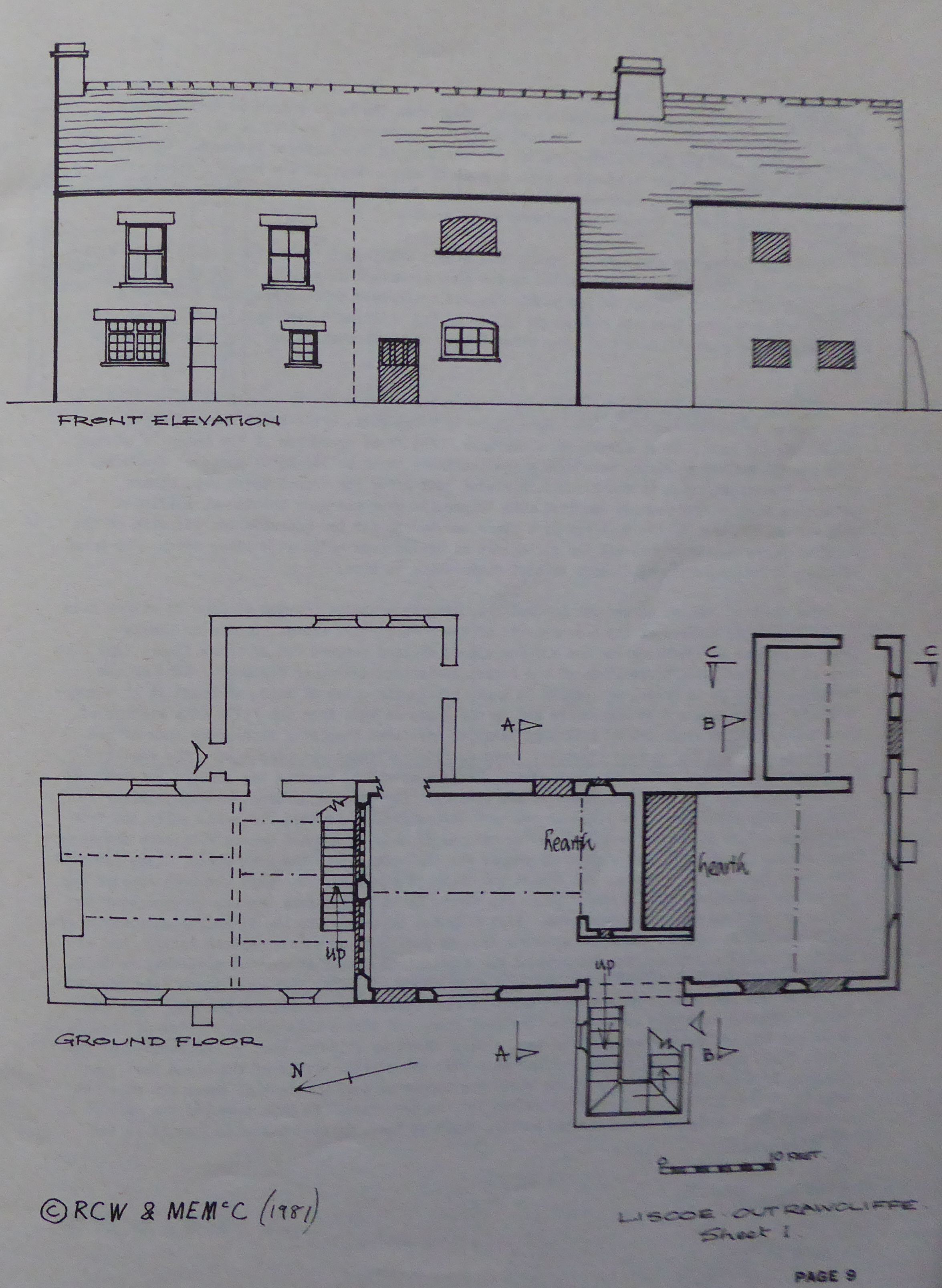

The room pattern on the first floor follows exactly that on the ground floor. The room over the parlour has an axial beam with very elongated leaf stops, a pattern repeated in rooms on the first floor with one exception. The most interesting feature of the room above the parlour is the comparatively large blocked-up hearth: its chimney formed an outer flue to the main hood (see above), eventually entering just below stack level. The room at the other side of the chimney stack also has a hearth, but of more modest dimensions.

There is an extensive floored attic, now entered through a trapdoor but which at an earlier stage would presumably have had a fixed ladder or small staircase, and which was probably used both for sleeping quarters and for storage. The main body of the house has two roof trusses, neither of them bearing carpenters' marks; one over either bay, and at each side of the corbelled chimney stack. The truss over the parlour end is of tiebeam principal rafter variety with a very low collar, supporting two inclined struts to the principals. Its partner over the housepart end also has a very low collar, supported by two inclined struts (of which one remains) from the tiebeam to the principal rafter. The truss in the rear wing (the service end) is of very makeshift construction and is presumably comparatively late: it is not clear at what stage this rear wing had its side walls raised and the pitch of its roof reduced. All the roof timbers are re-used, and it is very clear that some of them have formed part of a timber-framed house. Liscoe may be one of the quarter farms of Rawcliffe, and there could have been a previous building on the site, of post-and-truss construction and of generous scantling.

At Burn Hall, at Thornton (demolished in 1979) we had another capacious but three-unit, brick-built, house with a centrally-placed, projecting staircase turret, which contained a small room on each floor in addition to the staircase itself. The building had projecting chimney stacks on either gable and two projecting, two-storey bay windows to the front elevation. Whether these windows were of the original build or not is difficult to say, but if they were additions, the builder took trouble to extend the plinth, upon which the whole building was raised, around them. It is conceivable that the staircase turret was also a later addition. The woodwork in the house was well-formed and of heavy scantling, and some of the upper floor dividing walls were timber-framed. At the east end of the original house, in its last form abutting on to later extensions, was a remarkable first-floor parlour, which boasted a fine ornamental plaster ceiling decorated with vines and bunches of grapes. The second stage of the ceiling was the casing of its two beams with a plastered oak leaf and acorn pattern. This second-stage plasterwork appeared to be by a different hand and was on beams which, by the evidence of their moulding, were originally made to be seen. In this room was a stone fireplace surround which had a debased four-centred arched head, incorporating amongst the many motifs carved in stone the arms of the Westby family, (3) quartering other indiscernible arms. It was probable that this shield was originally blazoned because the existing raised heraldic symbols were insufficient in themselves to convey the true arms. Thornber records that until some period in the nineteenth century this room was panelled (4); and after its removal the room had been covered with layers of wash and wallpaper. The subsequent demolition of the building revealed what was fairly certainly the first plaster covering to the walls, and closer examination showed that the original decor had been a painted representation, in black paint, of timber framing. What was even more surprising was that the area above the hearth was painted to represent ashlar masonry.

On the other side of the river is Hackensall Hall, at Preesall, dated 1656, and built by the Fleetwood family, but now presenting the results of an 1870s' renovation. The original house was only one room deep and forms the front portion of the present building. There were originally three generously-sized units, and there are traces of what might have been an original cross- passage entrance. The main housepart contains some good early ovolo-moulded beams and has a lateral hearth. Some indication of the house's original appearance may be gained from the roof space, off the attic, which is over an outshut at the front of the house. The wall which divides this roof space from the attic is of handmade brick and contains a stone, two-light mullioned window of the seventeenth century.

Across the river again is Mains Hall at Little Singleton, built by the Heskeths, where there is, in the original surviving portion of the complex of buildings, a three-unit brick-built dwelling not dissimilar to Burn Hall except that the main room has a lateral hearth and stack. To the rear of this is a two-and-a-half storey gabled wing, added when the house underwent considerable cosmetic renovations in the 1860s. The roof space of the original portion of the house is interesting in that the two principal rafter tiebeam trusses have cranked tiebeams. The floor in the upper part of the later projecting wing is made of clay. Despite the house's comparatively high status, the original arrangement included a small formal garden at the front, which gave onto the farmyard immediately beyond, and culminated in a moat.

A little further up river on its south bank stood, until just before the Second World War, another moated site, Larbreck Hall, built by the Shuttleworth family. The house was of three units with projecting outshuts to the middle bay and a storeyed porch. Although we have no further evidence other than one photograph (5) as to the building's true age, it falls into the same category of size and height as the other houses under discussion and was probably of the same period.

Finally, a little further from the river and on its north bank, is Bowers House at Nateby of 1627, put up by the Green family (6). Here there is a two-unit, brick-built house divided, between the two main chimney stacks, by a corridor. The front elevation of the house is adorned by two small projecting wings, each with a small chimney stack on its outer corner. The house is on three floors and until it was covered in stucco just after the Second World War, showed projecting brick string courses combined with dripmoulds over the many bricked-up mullioned windows. At the rear of the building is a staircase turret far too generous for the size of the building it serves, which has all the appearance of having been added at a later date. The broad stairway it houses serves all floors without diminishing in size.

The question remains of why the landholders along this narrow stretch of land on either side of the River Wyre arrived at the arrangements of their respective houses, providing similar generous amounts of accommodation and working space, divided between two or three floors, and with such an individualistic disposition of the rooms, staircases and other features. None of the families, so far as is known, was native to their particular patch of land, although it is thought they all were in origin from Lancashire and in one instance were from the Fylde (the Westbys of Burn Hall), and the whole set of buildings seems to have been completed within the span of one generation. We can try various theories: were outside influences at play - were the families well-travelled and influenced by other areas? We have no way of knowing the answers but features in the houses examined occur elsewhere in the country: for example, a cross-passage similar to that at Hackensall Hall may be found in southern Lancashire, at Rufford Old Hall, while the twin projecting gables at Bowers House may be the outcome of copying grander houses with more developed cross-wings. Do we have here a group of people who all belonged to the same social class and were vying with each other to produce the newest and smartest dwelling? Whatever the true answers may be, we are confronted by a group of peers who strove to be individuals and who did not want to follow the main stream of current taste. What they had in common was the financial wherewithal to build substantial houses, probably replacing earlier dwellings of a less durable nature, and we should therefore ask ourselves what brought the substantial influx of capital necessary to build in the styles they established. We already have evidence (7) of an increase, lower down the social scale, of more substantial houses being built to what became the established pattern, such as Cocker's Dyke or Adamson's Farm, indicating that there was during this period a level of prosperity which was not confined to one class of landholder. There is evidence that in the decades of the 1590s, 1620s and 1640s there were poor harvests (8): the overall effect of these was that the smallest landholders tended to sell out while the larger or more substantial owner was able not only to survive but to obtain a better return for his own crops. He thus acquired the capital necessary for investment in bricks and mortar, which we have, in most instances, still in our midst.

REFERENCES

1. RC Watson & M E McClintock, Traditional Houses of the Fylde, Occasional Paper 6 of the Centre for North West Regional Studies (1979).

2. We are grateful to Mr and Mrs Andrew Parkinson for their kindness in allowing us access to their house.

3. Information about the Westby, Fleetwood, Hesketh and Shuttleworth families is to be found on pages 183, 140, 162, 422 respectively of J Porter, History of the Fylde of Lancashire (Fleetwood and Blackpool, 1876).

4. W Thornber, An Historical and Descriptive Account of Blackpool and its Neighbourhood, Preston (1840), p 312.

5. RC & H G Shaw, The Records of the Thirty Men of the Parish of Kirkham in Lancaster (Preston 1930), illustration facing page 150.

6. See Bulmer's History and Directory of Lancaster and District (Preston, c. 1912), page 296, for an account of the Green family.

7. Traditional Houses, op cit, pages 35 and 40.

8. See M Spufford, Contrasting Communities, CUP (1974), pp 50-51. She also describes, ibid, esp pp 51-3, the process by which smallholders were dispossessed and the larger landholders made more wealthy, in the period up to 1650.