Sand Fishing for Flukes

by Robert Parkinson and Rose Rabbitt

With his retirement in August 1972, Mr. Thomas Parkinson of Cockerham completed two hundred years of fishing history within his own family. This is his story and it is intended to illustrate just one aspect of his trade-sand or fluke netting for fish.

Sand or fluke netting is a method of fishing for flat fish which has been practiced in the Morecambe Bay area for many generations and probably dates back to before the time of the monks at Cockersand Abbey. There is no closed season and a fisherman may fish all year round, however, usually the weather dictates that he confines his fishing to the period from April to October.

Originally the fishermen made their own nets; this would be one of their tasks in the long winter evenings when fishing was poor. Cotton string was used; this was knitted into a diamond shaped one-and-three-quarter inch mesh in forty yard lengths to a depth of two feet six inches to three feet. The legal maximum length of a complete net when set, being three hundred yards. The depth of mesh ranging from three feet at the centre to two feet six inches at the sides. The centre, deeper portion of the finished net would comprise of say two forty yard lengths, the two lengths on either side of the centre would be shallower, and the outside lengths tapering off to two feet six inches at each end. Cord would then be threaded through the top and bottom edges of the completed net in order that it might be fastened to the stakes when the net was set. When completed, the lengths of netting and cords were soaked in tar and left to dry for some days. Such a net would last a season from April to October. Latterly ready made nylon netting was used; this of course lasted much longer. Stakes made of hazel or ash and, spars made of hazel were used to fix the nets into place, the former being one and a half to two inches in diameter and approximately five feet in length, the latter being three quarter to one inch in diameter and approximately four feet in length.

The setting of the net at low tide was carefully carried out so that the net would move with the incoming tide and re-set with the outgoing tide to trap the fish. The method used ensured that the deepest part of the net was in the centre of a semi circle in the drain channel of the water, the ends of the net being turned inwards to prevent the fish escaping around the ends of the net.

The stakes would be pushed or hammered into the sand at twelve feet intervals, in a semi circle and the net fastened by the cord to the top of every stake and to the top and bottom of every ninth stake. In addition, for every stake apart from the ninth stake, a spar was attached to the stake at the top of the net and to the bottom cord of the net. The positioning of the net in this way allowed the base of the net to move with the incoming tide and to return to the correct position for netting the fish when the tide turned.

It was usual for two or three men to work together when setting nets and the job would take three men approximately one hour to set one net.

Regulations laid down that a net must not be set across a freshwater stream or channel, that one net must not be set down within one hundred and fifty yards (150 yards) of another net and, that a small marker buoy must be placed at the seaward end of the net, also that the owner's name must be printed, painted or carved on the end stake.

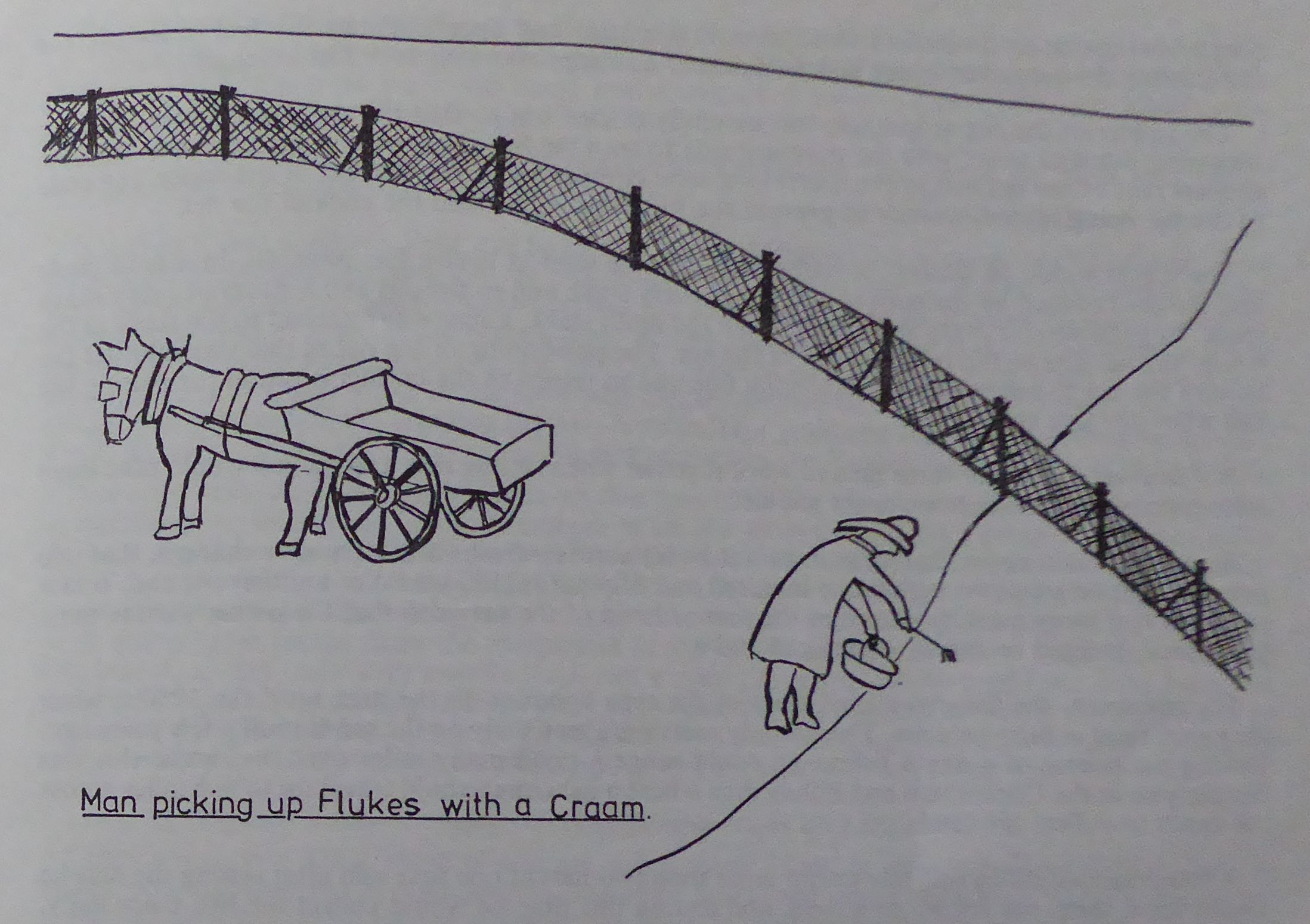

For transport, the fishermen used carts of the type common to the area until the 1930's, when they were used as farm vehicles. These sturdy carts were seen daily on the sands until a few years ago. During the course of a day a fisherman could range a good many miles over the sands, this was certainly so in the Cockerham and Pilling area where a fisherman could travel up to five miles across the sands to collect his catch.

A fisherman would be unlikely to run more than two nets at one time and after setting the nets he would leave them out for up to a week and during this time he would collect the fish twice daily, after each tide had receded.

The sizes of each catch would vary from two stone to forty stone of fish, an average catch during the season being twenty stone. Some of the fishermen sold their catch to retailers whilst others who had either a hawker's licence or a market stall would sell their own fish.

Today, there is little call for this type of fishing. Modern methods of catching and preparing fish have almost completely ousted this method of fishing except in the remoter areas. The life of the land fisherman was never an easy one and the younger man is unlikely to be attracted to the trade. It would therefore, seem inevitable that another generation will not replace the older generation in the trade, or will they?