Pilling's First Church

by W. Headlie Lawrenson

In the North West corner of a moated site approximately 100 yds x 60 yds a mound of rubble is all that now remains of Pilling's first Church.

Being situated in the midst of farmland about a quarter of a mile south of Pilling Hall and a similar distance from the nearest road, Horse Park Lane, with at present no right of access, the site is rather inaccessible. A road map of the late seventeenth century shows that in former times the chapel was served by a road running east from the junction of Lancaster Road and Horse Park Lane, at "Lane Ends Farm".

It is first mentioned indirectly in official records in 1272, but a petition to the Bishop of Chester in 1716 mentions an ancient tradition that the chapel was built around 1209, "when there was but seven families in the village". From these days it would be served and maintained by the Premonstratensian Canons of Cockersand Abbey who had a Grange at nearby Pilling Hall.

The monks of Cockersand had a special interest in Pilling, where according to local legend a party of colonising monks from Croxton in Leicestershire settled for a time, before receiving their foundation charter from Theobald Walter, brother of Hubert, Archbishop of Canterbury, of land in Pilling in 1190 and moving to the already established small "hospital" at Cockersand.

Some of the Pilling land seems to have been farmed by the monks themselves, for in a document of 1272 we learn that "during haytime the meadowland at Halkrigg and Pilling was measured, there was found to be in the Cellarer's meadow 23 acres to mow, in the Scister Scale meadow 44 acres,and in the chapel meadow, the Court meadow and the Moss meadow, 31 acres, and note well ther when the price for mowing the acre is threepence, we shall give for mowing the whole 24s. 6d. when the price is 31d. the acre for mowing, we shall give 28s. 7d. and when the price is 4d. the acre for mowing, we shall give 32s. 8d. for mowing and no more".

In the year 1493 a woman named Agnes Shepherd was granted a Bishop's Licence to live as a solitary in a cell at Pilling Chapel.

After the dissolution of Cockersand Abbey in January 1539 the sum of £2 per year was allowed for the maintenance of a curate, but this must have proved not enough, for in 1621 the parishioners of Pilling sent a petition to the King stating that although they paid tithes the chapel was neglected and no curate provided. The petition proved successful. £2 was granted out of Duchy revenues. Sir Robert Bindloss the lay rector made available £10 per year from the tithes, and the farmer of the demesne £6 13s. 4d., the parishioners themselves promising to provide a further £8.

In Commonwealth times the curate Mr. Lumley, who was appointed in 1639, was "silenced for several misdemeanours". Early in 1652 James Threlfall "a godly and orthodox divine" was minister. £50 per year was paid to the curate out of delinquent estates, the living having been vacant since 1650. During 1717 it was decided to build a new and larger church about one and a quarter miles to the west, which is now known as "The Old Church", in the present church-yard. This site was chosen for the convenience of the parishioners, as the petition for the re-siting states. "Such of the inhabitants as live westward of the present chapel were forced to go two miles on land not well to be ridden upon, being soft and mossy." It was added with a touch of pride that "there was not one dissenter in the chapelry". The new chapel was consecrated in 1721, leaving the old chapel and grave-yard to fall into ruin and decay. The only remaining gravestone at the present time is inscribed:

RICHARD SON OF CHRISTOPHER CLARK OF

THIS TOWN WAS BURIED HERE FEB YE JXTH 1720

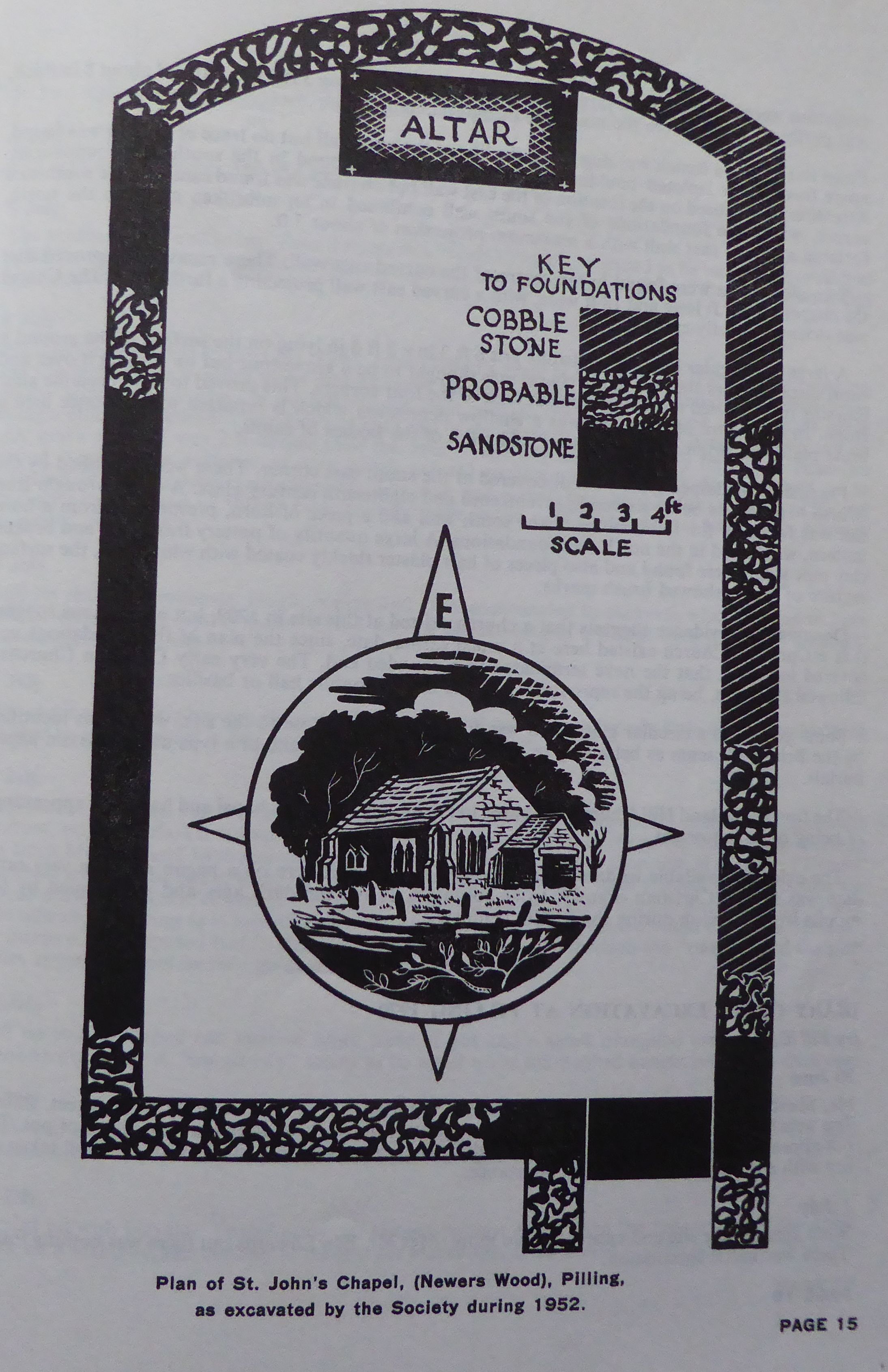

This site was investigated by "Pilling Historical Society" in 1953.

Diggings were made of a slight mound which was believed to be the central site of the chapel and human remains were found. It was noticed that the teeth showed no signs of decay, but were worn almost down to the gums, demonstrating the coarse food, mixed with grit from the millstones Pillingers must have eaten at the period. Further diggings were made and eventually masonry was discovered at a point which was later proved to be the north-east corner. These stones which were millstone grit and sandstone, were subsequently found to be outside the foundations of the chapel. Excavations to the west of this point revealed the foundations of the north wall. These consisted of dressed red sandstone blocks and extended 20 ft.

Diggings were made of a slight mound which was believed to be the central site of the chapel and human remains were found. It was noticed that the teeth showed no signs of decay, but were worn almost down to the gums, demonstrating the coarse food, mixed with grit from the millstones Pillingers must have eaten at the period. Further diggings were made and eventually masonry was discovered at a point which was later proved to be the north-east corner. These stones which were millstone grit and sandstone, were subsequently found to be outside the foundations of the chapel. Excavations to the west of this point revealed the foundations of the north wall. These consisted of dressed red sandstone blocks and extended 20 ft.

Attempts were made to locate the south wall, assuming that the chapel was only 10 ft wide, as had been reported some 15 years previously. But no trace of wall could be found at this distance from the north wall. A north-south trench was dug in an attempt to locate the south wall and this was eventually discovered at a distance of 18 ft from the north walls. These foundations consisted of water-worn boulders approximately 1 ft in diameter. Attempts were made to follow the line of the south wall but this proved difficult since remains were very scanty and consisted of boulders. No dressed stones were found.

A trench was then dug where the south-west corner was reported to be. Several blocks of red sandstone were discovered, the largest of these, a stone measuring 3 ft 6 in x 2 ft and about 8 in thick, was partly projecting from the main line of the foundations.

From this corner a trench was dug along the line of the west wall but no trace of walling was found, apart from a few isolated boulder stones similar to those found in the south wall foundations. Attention was focused on the location of the east wall but no trace was found except at the south-east corner, where the foundations of the south wall continued in an unbroken curve to the north, forming a curved east wall with a maximum projection of about 3 ft.

Two altar bases were found in the centre of the curved east wall. These excavations proved that the chapel was 27 ft long and 18 ft wide, with a curved east wall projecting a further 3 ft. The Chapel was oriented exactly east-west.

A large rectangular block of millstone grit 6 ft 3 in x 2 ft 8 in lying on the surface of the ground a short distance from the east of the chapel was thought to be a gravestone but on turning it over and cleaning it, an incised cross was found at each of the four corners. This proved to have been the altar stone. In the centre of the stone was a shallow depression which is reported to have once held a brass plate, but originally would have held relics of the bodies of saints.

Fragments of stained glass were discovered at the south east corner. These were identified by the British Museum as being sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth century glass. A large wrought iron rail was found in the foundations of the south wall and a piece of horn, presumably from a horn lantern, was found in the north wall foundations. A large quantity of pottery fragments and broken clay pipe stems were found and also pieces of hair plaster thickly coated with whitewash, the surface texture of which showed brush marks.

Documentary evidence suggests that a church existed at this site in 1209, but excavations suggest that a Christian Church existed here at a much earlier date, since the plan of the foundations un- covered indicated that the nave terminated in a rounded end. The very early Christian Churches followed this plan, being the reproduction of the Roman public hall or basilica.

Some years ago a circular glass bead was found in a ditch close to the site, which was identified by the British Museum as belonging to the fifth-seventh century and of a type used in Saxon pagan burials.

The font in Eagland Hill Church is reputed to have come from the chapel and has every appearance of being of Saxon origin.

The evidence available to date would perhaps suggest that here on a pagan site at a very early date was built a Christian oratory, to be forgotten during the dark ages and re-occupied by the monks from Croxton during the twelfth century.