In 1970, Mr. John Hallam, along with three others, excavated the skeleton of an elk from the Late Glacial period. In the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society for 1975, a Danish writer repudiates some of the conclusions made then the excavation was published. Dr. Tony Stuart has sent this reply for publication in L.A.B. and hopes to publish a more detailed refutation of the Dane's claims in a future issue of Proc. Prehist. Soc.

M.E.

Comments on the High Furlong Elk

Hallam et al. (1973) described an elk skeleton with two associated barbed points found in late Devensian (Zone II) deposits at High Furlong, Blackpool. Seventeen lesions on the skeleton were interpreted as hunting injuries caused by man-made weapons.

Noe-Nygaard, in a recent paper (1975, 15-16), however, has expressed the view that, with one possible exception, these lesions are actually of modern date. On the assumption that the bones were so decalcified as to be as soft as the enclosing sediments, she considers that the majority of marks resulted from damage by trowels etc. when the main part of the skeleton was excavated by 'enthusiastic amateurs'. Both the large number of bone injuries and the absence of flint fragments from postulated weapons are thought to be remarkable.

Even the clear lesion (no. 4) on the left metetarsal, in which a barbed point was found resting in situ (Hallam et al, 1973, plate VI), is thought to have been produced by compaction of the sediments forcing the implement into the supposedly soft bone.

In reply, three main points can be made :

(1) The bones were by no means as soft as assumed by Noe-Nygaard, and could not have been marked by trowels in the manner conjectured. They were after all sufficiently robust to be excavated both by 'enthusiastic amateurs' and trained archaeologists without the use of any field conservation techniques, other than the precaution of keeping the bones wet.

(2) Good lesions, including an elliptical cut on the right tibia (no. 8) are present on the hind limb bones which were excavated with great care by trained archaeologists.

(3) The lesion associated with a barbed point does not exactly replicate the shape of the weapon which was not in any case found embedded in the bone, but merely resting in the groove. Since the point itself consists of bone there is no reason why the metatarsal should have been the softer. Moreover several bones of the hind limb skeleton were found crossing over one another (Hallam et al. Fig. 2) and there is no trace of any marks at the points of contact.

In conclusion it can be said that, although the hunting techniques and nature of the weapons used are of course open to various interpretations, there are no reasonable grounds for doubting that the lesions on the High Furlong elk skeleton resulted from hunting injuries.

References : Hallam, J. S. et al., 1973. A Late Glacial elk with associated barbed points from High Furlong, Lancashire . Proc. Prehist. Soc., 39, 100-127.

Noe-Nygaard, N., 1975. Two Shoulder Blades with Healed Lesions from Starr Carr. Proc. Prehist. Soc, , 41, 10-16.

A. J. Stuart.

Painted Wall Plaster

The note on the wall plaster recovered from Newsham Hall Cottage, Woodplumpton, was included in Volume 1, number 6, although the plaster in fact came to light between twelve and fifteen years ago, because it had just then been returned after undergoing conservation, and was then for the first time ready to be placed on view in the Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston. As a result of that note, the following note has been submitted by Mr. A. K. McLerie of Poulton-1e-Fy1de.

M.E.

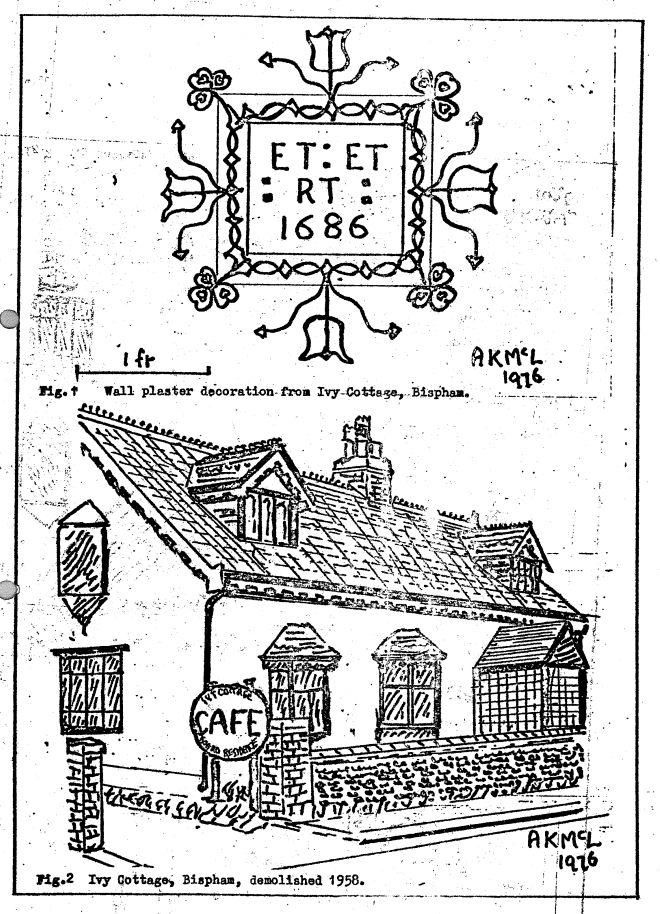

Ivy Cottage, Bispham

The drawing of Ivy Cottage, Bispham, (see fig. 2), shows it as it was just prior to its demolition in 1958. A piece of painted wall-plaster was recovered from the cottage (see fig. 1) and now is exhibited in Grundy House, Blackpool, the headquarters of the Fylde Historical Society.

The plaster is a clearly-dated example of seventeenth century decorative detai1; it, too, was taken from a cruck-trussed cottage containing several interesting features of traditional Fylde domestic architecture, and thoroughly examined and recorded by Mr. Richard Watson of Pilling. The colouring of the plaster is still just discernible and is as follows:

general background - light yellow; 'frame' background pale blue;

lettering and design - dark brown; design 'inside trefoils at corners dark blue'

A. K. McLerie.

Mr. Richard Watson of Pilling has submitted the following comments on the plaster of Newsham Hall Cottage, and on the structure of the cottage itself.

M.E.

Newsham Hall Cottage, Woodplumpton

If the date of the painted plaster (see L.A.B. 1,6,37) lies in the early seventeenth century, perhaps it is an example of 'putting out the bunting' for the 1619 peregrinations of James I - a suggestion which seems to be in keeping with the depicting of the supporters of the Royal Arms.

As for the building itself, it is full of enigmas, and may well be the remains of an earlier Newsham Hall itself. The evidence suggesting this is as follows.

When the south gable and chimney were re-built in brick, a cruck truss was removed. This is apparent because the wind-braces remained. When such an operation has been carried out, it is common to find evidence of the insertion of an intermediary support between the side purlins and the ridge purlin. Sometimes such supports remain, as here, in the form.

The piece here used was obviously an old item re-used; and it was finally realised that it was the upper part of an early type of cruck truss (see Smith, J. T. Vernacular Architecture 6, 1975 for his suggested pedigree). The earlier part of the building perhaps lay at the south side of the existing two units, and vanished years ago. The present central cruck, which had the painted plaster in its upper half, gives rise to several questions, to which answers can only be suggested.

First: why was the lower part of the tie beam incised with housings for small, irregular timbers, all with peg holes, and at various angles?

Suggestion: perhaps it is a later-devised backing for wainscotting.

Second: what was the original shape of the door which abutted onto and into the eastern cruck blade? The mortices and peg-holes for the rest of the frame are there but vacant.

Suggestion: the rounded shoulder which remains may indicate the only remaining portion of a four-centred, three-centred, or even an ogee-headed, arch.

At the rear of the building was an obvious extension in the form of an aisle with a four-foot eaves level. The interesting part of this extension was the wall which consisted of a wall plate, well-wrought, which had regular, well-wrought, closely-spaced studs fastened in with a peg. The tenons of these studs were held in a groove on the under-side of the wall plate - the whole of which suggests the sill of an old wall with some of its studs re-used upside down, their ends stuck into the ground. Close-set studs are not the earliest form of framed walling, but are certainly post-mid. sixteenth century.

R. C. Watson.

Mr. Watson has suggested that a manorial link could perhaps be established for the cottage through study of the field names as shown on the tithe map. Research into this has now been carried out but has go far produced no evidence of such a link.

Some Work Carried Out on the Danes' Pad, Newton-with Scales 1975

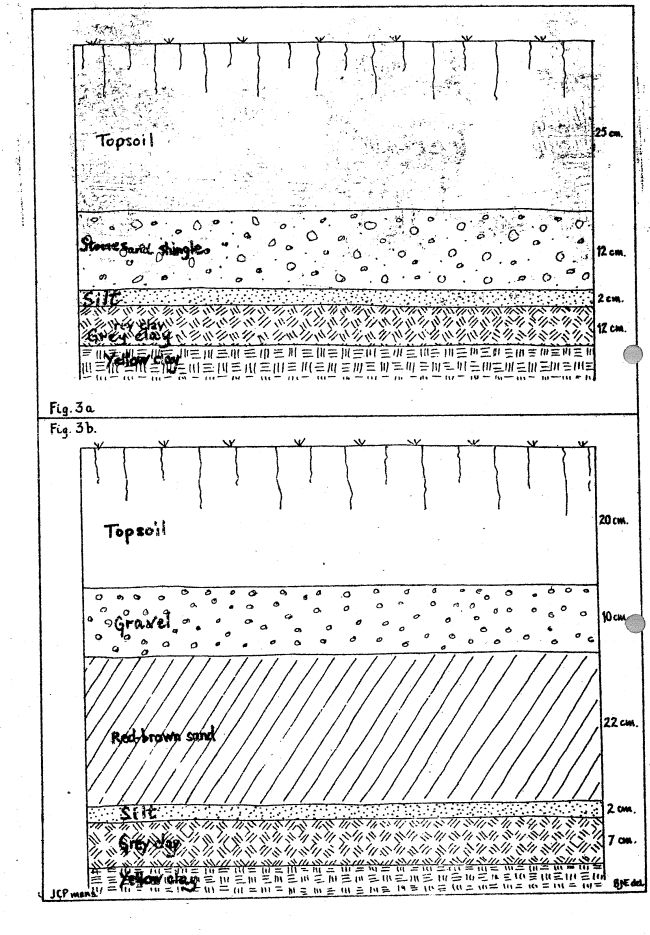

On 1st April, 1975, an excavation was made in a field at Moor Hall Farm, Newton, at a spot which coincided with information provided by an old O.S. map of Newton. First, probing rods were inserted into the soil; these encountered resistance at between twenty and twenty-eight cms depth. There is a short length of hedge to the south of the spot where the excavation was carried out; later, this was found to be the ditch of the road. For about nine metres northwards from the hedge resistance to the rods was experienced, so an excavation was made between the hedge and nine metres north of it. The diagram (fig. 3a) of the soil profile is explanatory, but at the northern end of the dig the grey clay was of greater depth, and the sub-soil was wetter than either the top-soil over the road or the grey clay below the shingle. Because of this, it is believed that this was the ditch to the north of the road.

At the southern end of the dig a similar situation was met with; there were also considerable quantities of sharp yellow sand, up to twelve cms in thickness, below the silt, which again was deeper here than in the middle of the road. The pattern of the stones strongly suggested that they had been placed there by human hands, and as this construction is on the line suggested by O.S. maps; it seemed likely that here were the remains of the Danes' Pad in this field. A little further to the west a layer of stones is noticeable in the side of a cutting made years ago; investigations with probing rods met solid resistance at similar depths to those previously mentioned. Investigations were carried out at intervals right across the field from the cutting to the hedge boundary with the field lying westwards of this one; resistance was met with at between twenty and thirty cms depth, for a total distance north-south of between twenty-one and twenty-three metres. The land to the immediate south of his cutting was then examined where it was seen to be higher than the land where the cutting was then examined where it was seen to be higher than the land where the cutting was. Therefore, probing rods were inserted south of the hedge; resistance was met with at no more than twenty cms for a distance of about nine metres southwards. An excavation here revealed the profile shown in the diagram (fig. 3b) as indicated the construction of this second road was entirely different from that of the first. This brought to mind the point made by W. T. Watkin in Roman Lancashire where the Rev. W. Thornber was quoted as having seen TWO roads side by side with a central ditch between them and a ditch on either side. Thornber had witnessed this at Dowbridge, about one mile west of the point where these digs were made last April.

On 19th October, 1975, the writer made an excavation at the western boundary of this field. This was not attempted sooner because the farmer was grazing cattle in the field and also because the very dry summer had left the soil in a very hard condition for digging. The road was apparent for about twenty-one metres width; it was strikingly obvious that the sandy road had suffered from plunder in the past much more than the stony one, as the sand could be more beneficial for soil improvement than stones and shingle. This also ties in with other comments by Watkin in his Roman Lancashire. The sand found in the cutting made by the author was of a very similar kind to the sand which the Kirkham hills appear to be made of. This sand was very obvious in 1968 when many tons were removed from the east side of Kirkgate in order to make the parking area behind the 'Concorde' and adjacent buildings.

Through the kindness and co-operation of several farmers, the author has been able to trace with probing-rods the track of the Danes' Pad from New Hey Lane, Newton, to the vicinity of Lund Church, but here problems have been encountered. In some places, the road has been almost completely obliterated, but it has been possible to trace its track between these two places. A dig in a harvested barley field on 25th October showed the remains of the road at approximately sixty cms depth; the digger found red sand, stones, grey clay and the yellow-brown clay of the area all intermingled. At this point, the road was running south of the church, and examination of the pathway in Lund Churchyard between the lychgate and a point halfway to the church door (the path turns sharply here to lead to the church door) showed several large stones on or about the surface of the path. These are in a line with the alignment of the Danes' Pad as suggested by the author so it appears that one road did in fact run south of the church. A dig was made on the east side of the church on the same alignment; results were the same as experienced to the west of the church. A further dig was made in the same field a point halfway between the previously-mentioned one and Church Lane; similar results were found here at about sixty cm. depth, suggesting another road south of the Danes' Pad. This one was pointing towards Station Road, Salwick, at a point about halfway between Lund Church and the windmill at Lund situated about fifty metres south of the crossroads of Church Lane, Deepdale Lane, Mill Lane, and Station Road. To substantiate this, probing rods were inserted into the soil along this new line, and resistance was felt at depths between fifty and sixty cms. That there are more roads in the area, seems likely for instance, most previous writers mention a road north of the church. A noticeable amount of sandstone is to be seen on the surface of fields in the vicinity of Lund Church, as well as rounded and hard stones; and the surface of many fields in Newton, Clifton and Salwick is very stony, (See fig. 3c)

The writer would like to express his thanks to the following people for their co-operation in providing information, or granting access to their land:

Mr. G. Cookson and family, Moor Hall Farm, Newton,

Mr. T. Benson, Coronation Villa, Moor Hall Lane, Newton.

Mrs. A. Worthington, ''Woodlands", Dingle Road, Newton.

Mr. and Mrs. R. Collinge, Dingle Farm, Newton.

Mr. C. Bradley, East View Farm, Vicarage Lane, Newton.

The Committee of the John Hornbie Charity, Newton.

J.C.Plummer

Agemundrenesse and Domesday

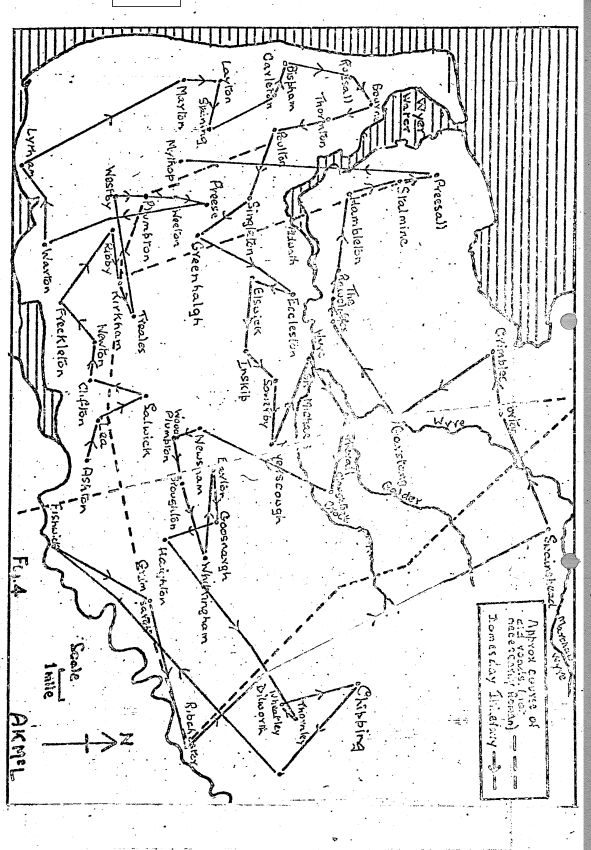

Looking through that 900-year-old list of strangely-spelled yet familiar 'vills' of Amoundersness as set down by William the Norman's Inquest Clerks (see V.C.H. 1 269), I wondered, as many others no doubt have done, how the information had been provided.

The information itself is not overwhelming, in fact, the treatment is jejune in the extreme. Only sixteen of the sixty-two vills of the Hundred inhabited? It seems almost unbelievable. Was it indeed surveyed at all? Or did the dykes and ditches of the Fylde, the shortness of time and the winter gales actually daunt the Inquisitors, so that they finally wrote, with sighs of relief, 'the rest are waste' - in the comforting belief that no-one would be going round to prove otherwise? Or was it that West-Lancashire-to-be, tug-of-war ground for ancient kingdoms, threap lands inviting invasion from south, north and west - was really down and almost out?

We shall never know; but what can we wrest from those reluctant pages of Domesday? We are not to believe, say the experts, that the Inquest Clerks went around from vill to vill, gathering the required information. It is doubtful we are told, if they even visited each Hundred.

If that is so, what are we to make of the order in which the vills appear in the final account? A great deal of it has the apparent form of an itinerary. Although we are discouraged from the belief, is it not possib1e that someone, if not the Sheriff or his deputy, did in fact make the journey from vill to vill throughout the Hundred?

This was an attractive thought, and to see where it would lead, the obvious step was to draw a map showing all the vills listed, and join them by arrowed lines in the order in which they appear in Domesday. (See fig. 4)

Immediately it became apparent that of the first thirteen vills, from Ashton to Preese, not one is far from the 'magna strate' Danes' Pad, which here follows the high ground of the crescent-shaped Kirkham moraine, and must at that time have offered a ready means of access into the heart of the Fylde. The next eight vills are on or near the coastal ridge, from the southern end of which a start was made at Warton; thence to Lytham; then northwards, to Biscopham (Bispham). Incidentally, one wonders what happened to warrant the ommision of Kellamergh and Bryning. Probably they were included in one or other of Westby, Ribby or Warton.

The most northerly coastal vill of Rossall is then reached, and the long return eastward commenced, on the left bank of the Wyre river, exchanging that river for the Brock at St. Michael's, to reach Catterall and Claughton. Some sort of track, precursor of the present-day A586, must have existed in those days, and it is along this section that two of only three churches listed in Amounderness are supposed to occur - Poulton and St. Michael's. The other Kirkham. These churches are not named; if there is a good reason for their identification thus, it is unknown to me.

The progression we have assumed now breaks down somewhat. The seven vills in the Barton/Whittingham group, and those in the Ribchester/Chipp1ng group, as also the outliers at Grimsargh and Fishwick, and the northern ones in Wyresdale appear to have been dealt with as 'pockets' ,

From Garstang onwards, however, some sort of progression is resumed, this time along the right bank of Wyre river to the estuary, keeping well away from the dreaded Pilling Moss, the extent of which, as used to be said, was exceeded only by God's mercy. At Hambleton the river turns northwards, and the Domesday list includes the vills of Stalmine ard Preesall. The Inquisitors no doubt utilised the track, distinct from the Danes' Pad and postulated by the late F. T. Wainwright from place-name evidence, running northwards from Kirkham, crossing the Wyre river - presumably at Aldwath - and continuing northwards along the right bank as far as the estuary. The claim to antiquity of this track is considerable, apart from the advocacy of Dr. Wainwright.

Finally, do we see, in the last entry, (Mythop) an item overlooked by the Inquest Clerks when making their first draft and inserted later? Whatever the reason, it is totally out of place, possibly a result of its position, on an 'island' , surrounded by mossland though within hailing distance of Danes' Pad.

A. K. McLerie.

Traditional Homesteads in Amounderness

It is very noticeable when conversing with people interested in local history that, although they are extremely knowledgeable about people and events and even the economic background of a given area, they seldom seem interested to know how families were housed. What knowledge they have in this field is usually based upon the romantic journalism we have for several decades been subjected to. This is despite quite a number of excellent readable books by eminent authors readily available from libraries.

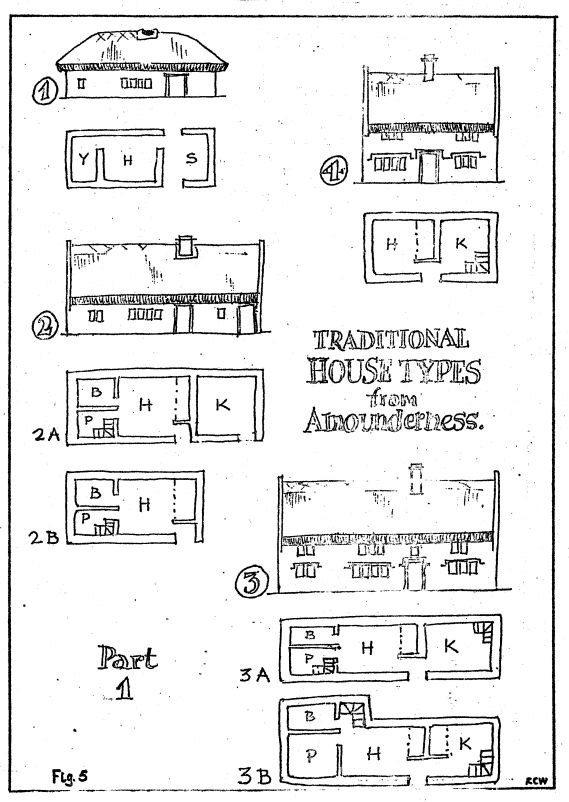

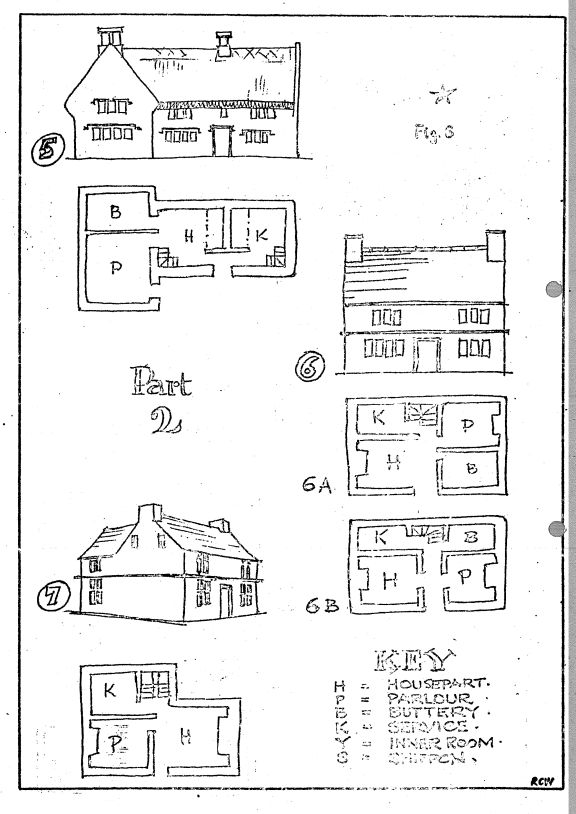

The following notes are intended as a very rough and ready guide to house types met with in Amounderness. The great house is not included, but the ground-floor plans and the elevations cover the large house, small house, and the cottage (See figs. 5 and 6). One must add a note of warning, however, because what is now classed as a cottage would not necessarily have been such when first built. The viewer's knowledge of the economic background to the area would have to guide him in this decision.

(1) LONGHOUSE

The earliest recognisable extant form of dwelling and shippon combined; it has a common entrance for man and beast. Up to the present time it has only manifested itself when later alterations have become apparent during a demolition. The type was probably in its death throes by 1600. Built of clay or stone on a timber frame.

(2) THE QUASI-LONGHOUSE AND DERIVATIVES

A natural development from the longhouse in terms of sanitation and comforts. It is still medieval in concept but has now a chimney of sorts and the shippon has a separate entrance. The type was established by the early seventeenth century and persisted, travelling down the social scale, until well into the eighteenth century. Plan 'A' was sometimes built with the shippon integrated, and used as a service room or workshop. Plan 'B' illustrates the two unit type without farm buildings.

(3) LATERAL HOUSE OF GREAT-REBUILD PERIOD

A more substantially constructed version of the three-unit plan, with an upper floor right through and often an attic if its status was high enough. Plan A' is the earlier type and plan 'B' a more sophisticated variation usually with a hearth in the parlour. Upper floor hearths are not unknown in the larger ones. The style appeared about 1670 and lost its general appeal about 1740. It did, however, continue to be built with slight variations until nearly 1800.

(4) UNIT HOUSE WITH CENTRAL HEARTH

A less popular Amounderness type which occurs with either an attic floor or a full upper storey. It can have one or two hearths on the ground floor and upper floor hearths are not unknown. Mid to late seventeenth century type which persisted until the mid eighteenth century.

(5) CROSS-WING HOUSE

A building of the Great Rebuild period which appears from the mid seventeenth century and does not occur after the first decade of the eighteenth century.

The room arrangement is in the traditional manner, but extra space for the now important parlour is gained by the use of a cross-wing.

(6) DOUBLE PILE HOUSE

Another house of the Great Rebuild. The plan occurs in Amounderness from the late seventeenth century, and persists, with sash windows superseding mullioned windows, until the early twentieth century. The plan can be very varied and plans 'A' and 'B' represent two of the earlier types. Originally in the large house group only, it progressed down the social scale as the years went by.

(7) SHAPED HOUSE

Occurs at gentry level only from about 1690. There do not appear to be many examples as yet recorded. The earlier houses are usually built upon a cruck-truss frame with walling of clay or cobble and occasionally rubble; some scant evidence of studded walls of early date occurs on the hilly perimeter. From the early seventeenth century brick and stone in varying bonds became the norm, descending the status divisions with the passing years. It Is worthy of note, however, that in certain areas of Amounderness clay walling was resorted to until the mid nineteenth century, The upper-cruck truss appeared at about the same time as the brick or stone loadbearing walls and diffused in their wake.

Some external timber framing can be found in the great houses of the area, but seldom has it been found lower down the social scale.

Many houses of the area are not freestanding, being attached to farm buildings of varying date, some antedating the dwelling and some postdating it, and all worthy of study.

R. C. Watson

Roman Coin Finds

Mr. W. J. Haworth of Accrington wrote an article for the Accrington Naturalists' and Antiquarians' Society's journal which was published in December 1971 (i.e. no, 3), a journal which is available mainly to members. He has submitted the article to L.A.B. as it will doubtless be of interest to readers, many of whom may well not know of the finds concerned.

Note on Two Roman Coins Found in Accrington

In spite of its proximity to the Roman Fort at Ribchester, no remains of that period have been found in our area, nor did any Roman Road pass through it, the nearest being the ones from Manchester to Ribchester through Blackburn, and from Ribchester to Elslack at Mitton.

In Accrington and its immediate vicinity, finds dating back to the period of the Roman occupation are virtually non-existent. It would therefore appear to be desirable to place on record two coins of the Roman Empire which have been found within the Borough.

When the house "Parkside", at the junction of Hollins Lane and Royds Avenue, was built (about 1930), a coin was found which is now in the writer's possession. Of slightly debased silver, 22 mm diameter, it is in excellent condition, showing on the obverse the 'radiate' head of the Emperor, with the inscription "IMP. GORDIANVE PIVS FEL. AVG." and on the reverse a personification of 'Equity' holding a Cornucopia and a pair of Scales, with the inscription 'AEQVITAS AVG,"

It is thus an 'antoninianus' of Gordian III, who reigned from AD 258-244, during what in Britain was a peaceful period following the rebuilding of the Wall by Septimius Severus early in the century. Little appears to be known about his reign, and he apparently never visited Britain. In common with all but two or three of the Emperors, Co-emperors, and usurpers of the third century, Gordianus met a violent death, being deposed and murdered in Mesopotamia at the age of twentyone.

A bronze coin was found in the same district in 1968 during the cultivation of a garden on the Laund Estate. This is 16mm in diameter, reading "D.N.FL.CONSTANS ---" around the bust of the Emperor, the reverse showing two soldiers with standards around which is the inscription "GLORIA EXERCITVS" (to the Glory of the Army) and is a nameless 'small bronze' or AE4 of the Emperor Constans (AD 337-350). A mint-mark in the exergue appears to read "RO", in which case the coin may have been struck at the mint of Rome.

Constans was the youngest son of Constantine I (the Great), and in 343 he visited Britain, the last reigning Emperor to do so, in order to repel the Picts and Scots. Whilst he was in Gaul in 350 his legions rebelled, Constans fled, but was overtaken and murdered at the foot of the Pyrenees.

In the absence of information regarding other possible finds of Roman coins in Accrington, the fact that the above two were found in the same locality can be of little significance. They apparently represent purely casual losses, by no means necessarily by Roman citizens or soldiers themselves, as the coins would at these times be in circulation throughout the whole of the native population.

W.J. Haworth

Mr. Haworth also mentions another find which he thinks is unrecorded. This came to his attention in 1973, though the find was made in about 1950. It was a sestertius of Commodus, with a figure of Genius on the reverse. (c.f. Seaby, 1540)

M.E.

Bronze objects from Cuerdale and Walton-le-Dale

Records exist of the finding of six bronze objects in the neighbouring civil parishes of Cuerdale and Walton-le-Dale, in the Ribble valley south of Preston, in the nineteenth century. It is the purpose of this note to try to resolve confusion which has since arisen as to the nature and details of the finds'

As so often, the early sources (Hugo 1853, Hardwick 1857) are the least obscure, much of the confusion having arisen through later carelessness. Hardwick says (1857:5) that 'about fifteen years ago (c ; 1842) a very superior bronze celt or axe, and a spear head of similar metal were found at Cuerdale by Mr. Richardson, the late tenant of the estate [and incidentally the man who saved and kept together the famous Cuerdale hoard of Viking silver, the largest of its kind outside Russia] whilst making a deep drain in what he termed the "cars or red water land"'. Further, he adds (1857:7) 'The ordinary celt, fig.6 plate I, was found at Walton, together with the bronze articles, figs. 3, 5 and 9. These last three items are respectively a pierced late Bronze Age hollow casting of disputed function ("harness fitting" - for which see below); an Iron Age mirror handle of Northern English type; and a spear head.

Of the six objects, four survive in the Harris Museum, Preston. They are : 1. A socketed axe - Reg. No. A. 136. 2. A spear head - A. 127. 3. The "harness fitting" A. 140, 4. The mirror handle. The only real problem lies in the identification of the spear head and the axe.

It is a priori more likely that they should be the Walton examples rather than the Cuerdale ones, because Hardwick states that all four Walton objects 'were deposited in the museum of the Literary and Philosophical Institution, Preston' (1857:7). There seems to be no published illustration or detailed description of the Cuerdale objects prior to a date when some of the six objects were in a Preston museum. Any subsequent descriptions (e.g. Garstang 1906) do not help, as they are of the surviving objects, and do not prove or disprove their attribution to Cuerdale or Walton. Thus we have Hardwick's clear statement that his illustrations are of the Walton objects, together with the additional fact that the Cuerdale axe 'was forwarded to London for the inspection of some archaeological society and a common one of the form of fig. 6, plate I [the Walton axe] returned in its stead' (1857:5).

We may, therefore, compare the surviving objects with Hardwick's plate I. The representation of the mirror handle and "harness fitting" suggest that he was fairly accurate, and on this basis the spear head A.127 is about an inch too long for the Walton object. The axe-head, A.136, too, is not 'a common one of the

form of fig. 6, plate I', but an example of the 'Yorkshire' type with three ridges on the face. It appears, therefore, that the two Cuerdale objects have survived together with the "harness fitting" and the mirror handle from Walton.

Garstang (1906 : 233) rather adds to the confusion by describing a socketed axe which corresponds well with A. 136 as having been found 'at Walton-le-Da1e. (in the parish of Cuerdale)'. This could be read as implying either (a) that Walton-le-Da1e lay in the parish of Cuerdale, which is not the case or (b) that the objects were found in that part of Walton-le-Da1e called Cuerdale which would be possible, apart from the inaccurate use of the word parish, since Cuerdale formed part of the ancient chapelry, later parish, of Walton-le-Da1e. He goes on to refer to the 'decorative ridges', says that the axe is in the museum at Preston, and concludes that it is the one found at Cuerdale in 1838, giving a reference to Arch. Journo viii, 331-2, which should presumably be to Hugo (1853) In J.B.A.A , viii, 331-2.

Reference to Hugo (1853) gives the information that the two Cuerdale objects were found in the same field as the 1840 Viking hoard, in 1838 (the axe, 380 yards from the Viking hoard site) and 1840 (the spear, six months after the Viking find, and three yards from the axe.)

It will be obvious, therefore, that although there would be nothing inherently improbable about the finding of A. 127 and A. 136 together, they cannot be associated more closely than three yards and two years apart. Similarly, the "harness fitting" and the plain socketed axe would be a reasonable association, but doubt is thrown on Hardwick's use of the word 'together' by the existence of the mirror handle. It looks as though 'together' means no more than that the four objects specified on plate I of Hardwick's work all came from Walton-le-Da1e,

It will be observed that it is curious that two objects of different classes, which were said in 1857 to be in a Preston Museum, have disappeared, while two objects of the same classes which Hardwick did not illustrate in 1857 have apparently survived. Either this is the case, or confusion had already arisen less than twenty years after the Cuerdale finds.

References :

Hugo, 1853 - JBAA viii, 331-2.

Hardwick, 1857 — History of Preston.

Garstang, J. (1906) VCH Lancs 11.

Miscellaneous Notes

5. Mr. McLerie of Poulton mentions a matter which has just come to his attention. A large anchor, made almost entirely of wood, dredged from the river bed at Fleetwood just after the end of the last war, at a point near to where the Isle of Man boats used to tie up. This find has been confirmed by a native of Fleetwood. It may or may not have a connection with Spanish gunboat known to have anchored in the Wyre mouth during the Civil War; the ship's guns were appropriated reputedly by the and itself destroyed by fire. Unfortunately, as the whereabouts of their anchor are entirely unknown, the connection cannot be proved or disproved.

6. An Ancient? Monument

Among the scheduled Ancient Monuments of Lancashire is the Packhorse Bridge at Brooks Farm, Bleasdale. This is a narrow, single-arched bridge over the river Brock, and, despite the general difficulty of dating such structures, seems a reasonable candidate for inclusion in the list. Some doubt, however, is thrown on this conclusion by its absence from the first edition of the Ordnance Survey 6-inch map of 1846. A ford only is shown at this point. Comparison between the 1846 map and the first edition of the 25 -inch map of 1893 (fig, 9) shows that, between these two dates, the present private road bridge was built, slightly downstream of the earlier ford, while the sheepfolds to the north of the river were rebuilt and the 'packhorse' bridge erected on the site of the ford. One can only presume that the purpose of the bridge was to facilitate the handling of sheep, and that its date is somewhere in the second half of the nineteenth century.