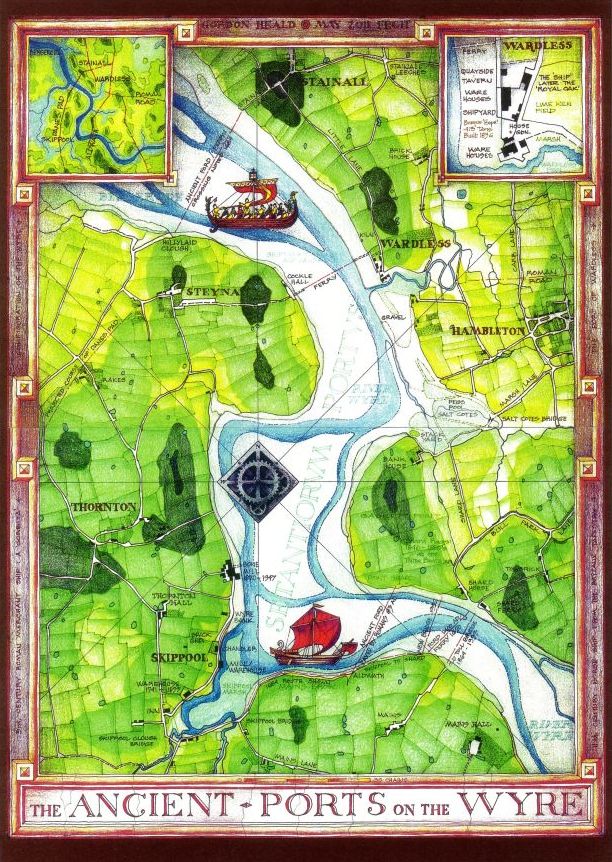

Map 13 The Ancient Ports on the Wyre

The stretch of Wyre between Wardleys and Skippool, the highest navigable point and coincidentally the lowest crossing point, has always been a strategically important communications hub and a vital link in the ancient coastwise north - south route. Two Roman roads converge upon it: the link north of the Wyre from the main Walton-le-Dale to Lancaster road at Garstang via Nateby to Wardleys and the southern route from Ribchester via the Fort at Kirkham and the Dane's Pad to Stanah. Both have been traced on the ground in recent years; the former by Pilling Historical Society and the latter as far as Puddle House Farm near Poulton by Philip Graystone ( CNWRS; 'Walking Roman Roads in the Fylde and Ribble Valley' ). A possible third, running due north from Kirkham and crossing the Wyre at Windy Harbour, awaits investigation.

The numerous ferries and fords, from the ancient crossing at Stainall to the Roman ford at Aldwath and the more recent crossings at Shard, are well known and have all left their traces. The obviously engineered slope of Stainall Lane is less well known than most others and would repay further examination.

In the second century AD, Claudius Ptolemaeus (Ptolemy) of Alexandria published a map of the entire known world, including the British Isles, which listed the latitude and longitude of every place of importance. One such place is the Setantiorum Portus, the port of the Setantii, which appears to be located somewhere near the mouth of the Wyre. Much time, thought, ink and paper has been expended on the interpretation of Ptolemy's figures but, all factors considered and weighed, the particular area between Wardleys and Skippool fits best of all, despite serious but discredited attempts to place it offshore near King Scar, or even at the other side of Morecambe Bay.

What was the nature of this port? Was it already in use by the local tribe, the Setantii, before the Romans arrived (which its name may indicate) or was it founded and developed by the Romans themselves? Roman roads certainly lead to it and the Roman fort at Kirkham, astride the old north-south route, would control and protect it. In either case, in ancient times and indeed until the 19th. century, because of the extreme difficulties of overland transport, the natural and preferred location for ports was as far up river as possible rather than out on exposed coasts subject to stormy seas. Roman merchant ships, the Corbitae, would certainly have reached this far on a flood tide.

The practical argument in favour of the Wyre as a location was then the same as that for the later establishment of the port of Fleetwood in the 19th. century - the old sailors' adage '' as safe and easy as Wyre Water ''.

During the centuries following the fall of the Roman Empire the west coast of England was under continuous attack from sea raiders based in Ireland and Scotland, and they may well have penetrated as far as the hidden port up the Wyre, which they might actually have already visited as traders. Certainly by the 8th. or 9th. century Viking longships would have been seen in the Wyre and the entire area became part of the Irish Sea Hiberno-Norse cultural zone. Norse occupation of the area is well documented and place names such as Skippool indicate its use as an anchorage and landing place. It has also been suggested that the name Thornton indicates the end of a Norse trade route and the Danes' Pad may owe its name to its use by Norsemen during this period. Intriguingly, it is possible that the lost battle of Brunanburh may have taken place nearby.

Trade obviously continued through the middle ages although records are sparse until the 16th. century when cargoes of flax and tallow are recorded as being landed.

Poulton, the ancient settlement and local metropolis with a church dating back to the 11th. century and possibly pre-conquest, then became regularised as an official landing place under the port of Chester (and later Preston) because of its recognised harbours of Skippool and Wardleys and landing place at Mains Brow. Trade flourished and Customs offficials were based in the town with a watch house near the entrance to the Wyre at Knott End.

Trade with Russia, the Baltic, the West Indies, Scotland, South America and other parts of the world is recorded, with quays and warehouses being built to accommodate cargoes such as tobacco, sugar, rum, flax, cotton, oranges, grain, timber, slate, coal and so on. Even a nodding acquaintance with the darker side, the slave trade, is acknowledged. The building of ships up to 400 tons was undertaken and associated trades such as rope walks were established. Poulton was full of inns, Shard became a venue for horse racing and Skippool became notorious for cock fighting; in fact all the activities and trades connected with successful ports were established.

This uniquely favoured location had thus continued in use as a flourishing port for many centuries until replaced by the establishment of Fleetwood further down river, an artificial construct able to take much larger ships but only made possible by the coming of the railways and, ironically, soon made redundant by their further technical development.